I'd guess that Delano attracted the attention of the boys before he took their picture. As these two details show, they seem happy to be photographed as much as they're happy to have climbed to an ideal viewing spot.

In one of his first assignments for FSA Delano had used his camera to document laborers and laboring communities along the U.S. east coast. Starting in Florida, he'd worked his way to the nation's north-east estremity — Aroostook County along the border with Canada. All his photos in this set come from the FSA/OWI Color Photograph collection in the Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. As usual, click to enlarge.

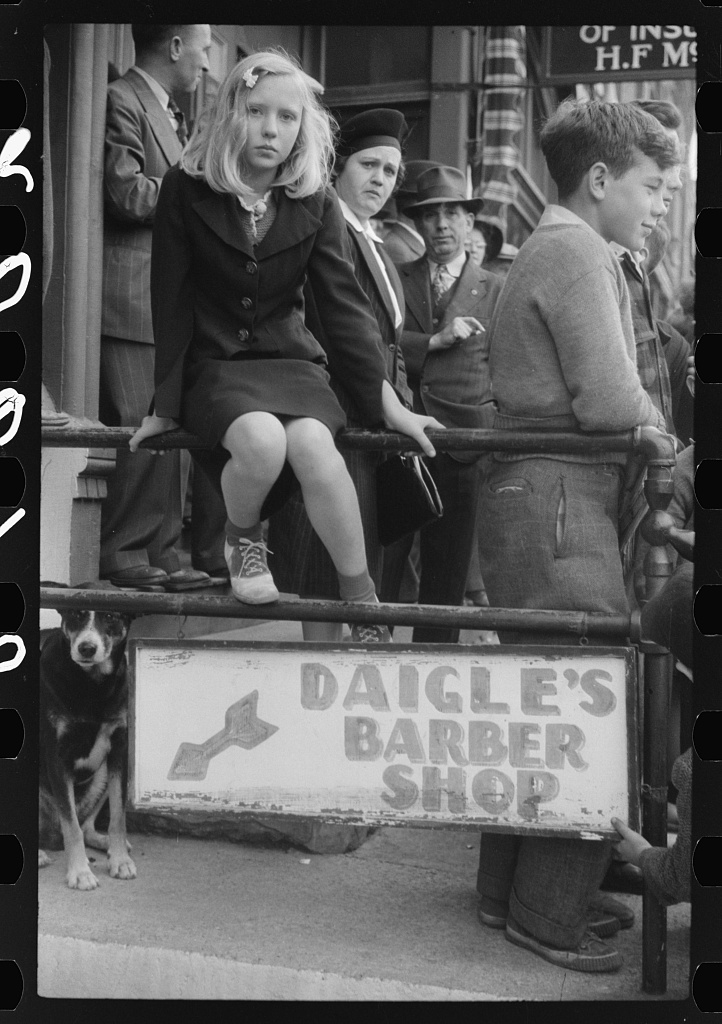

Although this set of photos shows us the contest itself, Delano seems more interested in the people who turned out to watch it.

In the following photo, the boy who's looking at the camera would probably have been happier mingling with the kids on the roof of Chesley's Electric Service.

The next photo seems to have a post-modern sensibility. It's not about the event or even about watching the event. It seems to some degree to be an abstract display of contrasting tones and textures and an exercise in handling negative space (the light colored areas, particularly among ankles and feet) but basically I suspect he wanted to see whether a photo of people's backsides would succeed, could be at all visually satisfying.

On the other hand it might have been a kind of inside joke. In an interview some 25 years later Delano said his boss would give detailed instructions before sending photographers out on assignment. He'd give them books to read and give them things to look out for, like "there is a certain drugstore on such and such a corner which has a certain thing in the window which you must be sure to find" and even "what kind of shoes" the people wear. He'd expect Delano to absorb all this information but he also expected him to be observant and to make his own judgment about what to shoot and how.*

The caption of this one says these girls are high school students who are participating by holding spuds on the ends of sticks. At left you can see a barrel sculpture, the "pototem pole."

The caption says the string that the Boy Scout is holding is the finishing line for the barrel race.

Here Delano shows the contest itself. Notice the news photographer on the back of the pickup truck and, just in front of him, the barrel with its potatoes. The caption says a full barrel weighs 200 pounds.

Detail from the previous image:

In this shot you can see more of the spectators and their reactions.

Detail from the previous image:

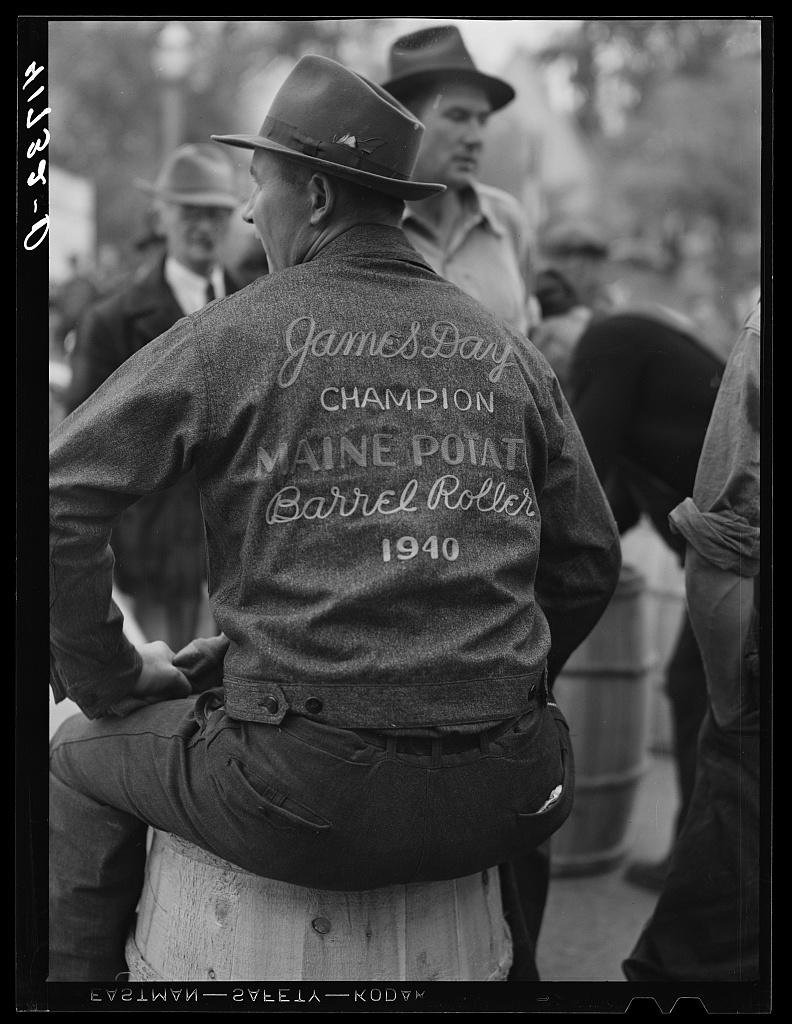

Here are two more photos from the many Delano took that day. The first is a poster advertising the contest and the second shows a champion roller. The caption says the latter shows "James Day, ace barrel roller and idol of Aroostook boys."

----------

*

Here's the relevant section of the interview:

[Interviewer:] We get these stories about how Roy would give you all sorts of books to read, and give you personal lectures and shooting scripts, and all that sort of thing. How much of that is correct?

JACK DELANO: Well, that's basically correct. I think that's quite true. Roy gave you the feeling that he knew more about everything that you did and, above all, ha knew more about America that you did, by far. And that's one of the things that I loved about Roy and one of the things I got most from him was a feeling about the United States, about America. This enthusiasm and love for the detail and the deeper meaning of everything American was something that he must have transmitted to everybody. He certainly did to me. In preparing for an assignment he not only gave us books to read, and all kinds of other things, but would talk and talk and talk in great detail about what you will find up there, and what you must look for, and there is a certain drugstore on such and such a corner which has a certain thing in the window which you must be sure to find, and so on. And he almost always would end up in saying, "But, of course, if you don't find any of these things, you do what you want to anyway." This is the way it always ended and frequently, after lengthy and detailed instructions and shooting scripts that Roy would develop, if you got up there and found that there was something else that interested you, and something else that you felt was more important and more pertinent, you just went ahead and did it; and wrote to Roy and said, "Look, Roy, it isn't like you said." This was perfectly okay with him because he wasn't imposing his ideas on you; he was trying to get you stimulated enough so that you would find out what was really there.

Interviewer: There was no dictation, I mean in this whole business he was simply trying to get you started. He didn't care if you went off on your own and took a different slant?

JACK DELANO: Not at all. On the contrary, he was trying to stimulate you to do that. In some of his letters, which we will show you -- I'm sure we'll find them this afternoon -- he would write in longhand these long letters in which he would work out for you a complete shooting script on what you should be looking for in Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania or in Aroostook County, Maine. He would write in great detail about potato-picking, and what kind of shoes do they wear, and what kind of gloves do they wear, and where do they eat and sleep, and do all sorts of other things. But this was primarily a guide for you to open your eyes and be looking for these things. He wouldn't tell you what to photograph at all, ever.

-- Oral history interview with Jack and Irene Delano, 1965 June 12, An interview of Jack and Irene Delano in Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico, conducted 1965 June 12, by Richard Doud, for the Archives of American Art.

----------

Some sources

Jack Delano, 83; Depicted the Depression, an obituary in the New York Times by By Margarett Loke, August 15, 1997

Harvesting Potatoes, text by Richard E. Rand, images from Aroostook County Historical and Art Museum, Presque Isle Historical Society and Southern Aroostook Agricultural Museum

Aroostook County, Maine. October, 1940. Aroostook County, one of the largest potato producing centers in the world Photographed by Jack Delano for the Farm Security Administration. A collection of 160 photographic prints in the Library of Congress. Summary: Photographs show Aroostook County, one of the largest potato producing centers in the world. Aerial views of fields and farms, during harvest season. Tractor and horse drawn diggers. Crews of men, women, and children. Storage barns. Loading railroad cars for shipment. Isolated potato seed foundation farms. FSA community seed program. Demonstration of cutting and planting seed potatoes. Starch factory. Homes and families of French-Canadian farmers. Portraits.

Oral history interview with Jack and Irene Delano, 1965 June 12, An interview of Jack and Irene Delano in Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico, conducted 1965 June 12, by Richard Doud, for the Archives of American Art.

Farms in the Aroostook County, Me., Oct. 1940 : potatoes, Library of Congress

Farms in the Aroostook County, Me., Oct. 1940 : potatoes, Flickr photos from the Library of Congress

The Potato Culture of Aroostook County, Maine, USA

Aroostook Potatoes on aroostook.net

The Maine Potato Barrel Story

Extract: "The potato barrel is native to Aroostook, Maine's largest county; once the nation's largest producer of potatoes. While the other potato producing areas used burlap sacks, Aroostook farmers used the good, tongue and groove cedar barrel. It was used in the field during harvest and in the storage and sold by the barrel; they still are in Aroostook where farmers figure the cost of potatoes by the barrel. Although automated harvesters have taken over the bulk of the work, there are fields, even today, where barrels can be seen strung out in rows for the pickers to fill. Men, women and children-even grandparents bend to the task. An even today, children are excused from school for several weeks during this most important event."

Teams And Technology Educating Researching Aroostook County Tubers

Extract: "The history of the Maine potato industry reveals an industry of great change as illustrated by the number of farmers in business in the early 1900's compared to the early 2000's. The report titled, "Aroostook: Potato Capital of America" states there were over 6,000 farmers devoted to raising potatoes in Aroostook County, Maine around 1930-1940, while another report titled "A Study of the Maine Potato Industry: Its Economic impact 2003" reports only 586 potato farms in Maine in 1997."