This one dates from about the same time.

Although digital imaging can be somewhat flakey, I imagine you can tell that these two make good use of a wide range of color tones.

Impressed on newsprint using high-speed, multi-cylinder rotary presses, advertisements in the local press couldn't attain such high quality. But, even in 1909, they looked pretty good, as this page from the New York Herald of 1909 attests. You can assume it looked a lot better on the day it came out. The highly-acidic wood-pulp paper on which it was printed will have deteriorated much more during the past century than the heavier stock on which the cigar and Coke ads appeared, and as the paper aged the colors will have grow dim.

Newspaper color work from earlier in the 19th century is also surprisingly good. This example comes from a New York weekly, Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, in 1883.

This one comes from more than a decade before.

Many newspaper illustrations were what we call political cartoons. This patriotic example appeared in the New York Herald on January 9, 1898. It isn't usually identified as typical of the era's yellow journalism, but this cartoon does fit the mold pretty well. When it appeared the high-circulation dailies, such as Hearst's New York Journal were flaming American jingoism and the Spanish American War was just about to break out.[2]

This 1895 drawing shows a multi-cylinder color press. These presses printed multiple colors in one operation at high speed.

These presses were enormous and immensely complicated. Containing about 50,000 separate pieces, they were something like thirty-five feet long, seventeen feet high and twelve feet wide. Although they used only four colors, they'd have some 64 sources of ink, called fountains. Fed by huge rolls of paper, they build up a color illustration by overlaying first yellow, then red, then blue, one after the other. The paper wound its way through the press much too fast for the different impressions to be visible, but if they were you would be able to see what the following images show. Note that the fourth color, black, is not part of this somewhat simplistic demonstration of the overlay process.

Modern industrial progress by Charles Henry Cochrane (J.B. Lippincott company, 1904) }

Although the process was highly automated, a great deal of skill was required in creating the plates from which each impression would be drawn and setting up the press to insure that the plates and unrolling paper were precisely aligned.[3] In most cases the artist would create the original color work using pen and ink or brush and paint. The work would be photographed three or more times using color filters to isolate, respectively, the yellow, red, and blue tones, and their variants. By a process called photoengraving, the photographic negatives (all of them black and white) would be used to make at least three printing plates and these, in turn, would be used to make the stereotype plates that were attached to the rollers of the giant presses. Each stereotype printing plate would be inked with a separate color to impress the paper as it wound its way through the press.[4]

The cigar and Coke ads were not made on one of these presses. They were poster-sized placards meant for display in shop windows, on advertising kiosks, and the like. The Coke ad was made by a process called chromolithography. In the late 19th century, chromolithographs were called "chromos." They were color lithographs and their quality varied greatly, depending on the skill of the printers and the size of the project's budget. The best were costly and could be extremely faithful to the original. They were made either by repeated impressions of a flat sheet of paper against inked lithographic stones or by a rotary method called offset lithography. A book published in 1875 describes this process clearly and in some detail.[5]

This enlargement from the Coke ad shows the tonal gradations that could be achieved in a relatively high quality chromo print.

The Newsboys Cigars ad has more abrupt tonal gradations. Although the curator identified the ad as a lithograph, the enlargement I've put below shows that it has been reproduced via halftone process. While chromolithography was done on lithographic flatbed or offset presses, halftone printing could be done on letterpress printing equipment, the same type of presses that were used to publish daily newspapers. In halftone work, tonal gradations are conveyed by dots of pigment. When the dots are close together the eye sees relatively intense tones; as they're increasingly separated, the eye sees lighter tones of the pigment. Making high quality halftones is difficult and time-consuming, requiring exact registration of the paper through multiple impressions, but the process is nonetheless cheaper and faster than is high quality chromolithography. Half-tone illustrations could be inserted along with text on the pages of daily newspapers, but this would normally be done for black and white photographs rather than color pictures.[6]

Here is an enlargement from the cigar ad that's comparable to the one of the Coke ad.

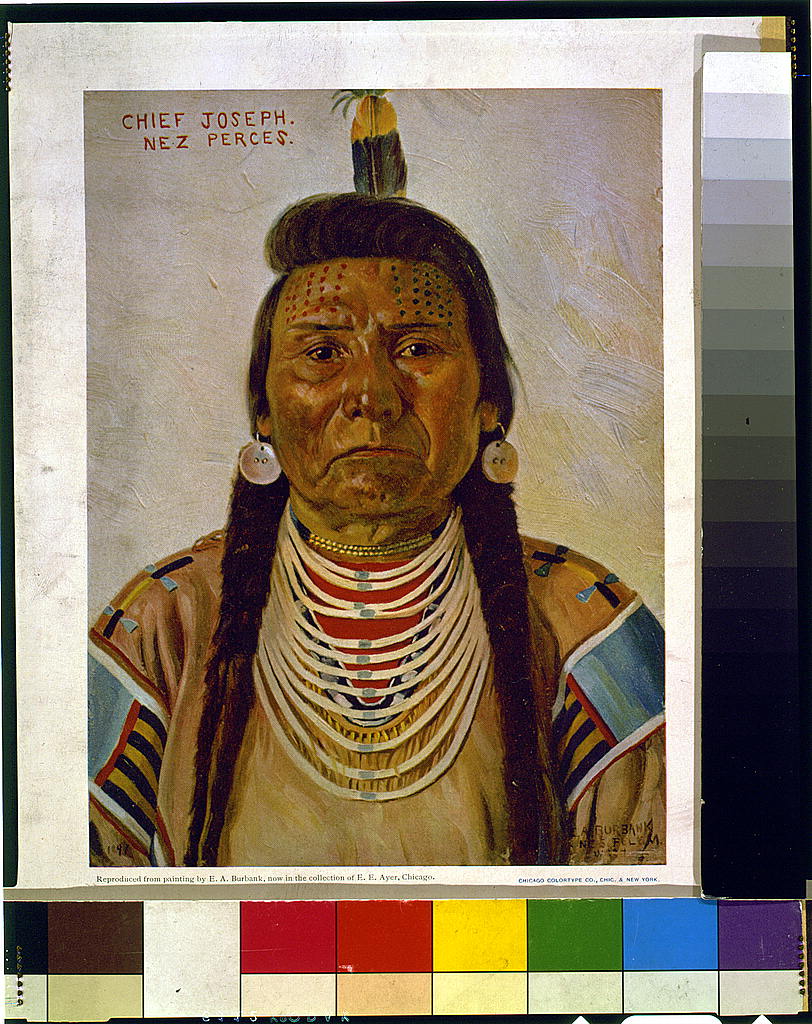

Compare this detail from a halftone reproduction of a painting of Chief Joseph made in 1897.

Here's the painting from which I've taken the Chief Joseph detail. Note that in this case the Library of Congress curator has identified the print as a halftone.

The New York Public Library has an excellent set of web pages describing and demonstrating chromolithography. Note in particular its sets of progressive proofs of a print called Prang's Prize Babies.

The two small crosses that you may have noticed on the Coke ad show it to be a type of proof. The crosses helped the printer determine that the registration was accurate as each successive color overlay was made. Once exact registration was assured, the crosses would, of course, be removed so as not to appear in the production prints.

-----------

Some sources:

The New Journalism 1865-1919

The Penny Press

Six thousand years of history see other blog post

The Daily Newspaper in America see other blog post

"Printing Presses" in The Encyclopedia Americana Encyclopedia Americana Corp., 1919

"The Development of the Rotary Web Press" in The American manual of presswork Oswald publishing company, 1916

Modern industrial progress by Charles Henry Cochrane (J.B. Lippincott company, 1904)

Color printing in wikipedia

History and present condition of the newspaper and periodical press of the United States by Simon Newton Dexter North (Govt. print. off., 1884)

American dictionary of printing and bookmaking by Wesley Washington Pasko (H. Lockwood, 1894)

History of Color Printing

COLOR PRINTING IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY An Exhibition at the Hugh M. Morris Library, University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware, August 27 - December 19, 1996,curated by Iris Snyder

The wonders of modern mechanism, a résumé of progress in mechanical, physical, and engineering science at the dawn of the twentieth century by Charles Henry Cochrane (J.B. Lippincott company, 1900)

Chromolithography on wikipedia

"How Chromos are Made" in The living age, Vol 95 (Littell, Son and Co., 1867)

"Chromo-Lithography" in House documents, otherwise publ. as Executive documents, 13th congress, 2d session-49th congress, 1st session (Gov't Printing Office, 1876)

The half-tone process: A practical manual of photo-engraving in half-tone on zinc, copper, and brass by Julius Verfasser (Iliffe & sons, limited, 1904)

The chemistry of light and photography: in its application to art, science, and industry by Hermann Wilhelm Vogel (London, Henry S. King & Co., 1875)

Commercial engraving and printing, a manual of practical instruction and reference covering commercial illustrating and printing by all processes, for advertising managers, printers, engravers, lithographers, paper men, photographers, commercial artists, salesmen, instructors, students and all others interested in these and allied trades by Charles William Hackleman (Commercial Engraving Publishing Company, 1921)

--------

Notes:

[1] Wikipedia gives a bit more detail: '"Drink Coca-Cola 5¢", an 1890s advertising poster showing a woman in fancy clothes (partially vaguely influenced by 16th- and 17th-century styles) drinking Coke. The card on the table says "Home Office, The Coca-Cola Co. Atlanta Ga. Branches: Chicago, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Dallas". Notice the cross-shaped color registration marks near the bottom center and top center (which presumably would have been removed for a production print run). Someone has crudely written on it at lower left (with an apparent leaking fountain pen) "Our Faovrite" [sic].'

[2] Contemporaries news readers didn't use the term yellow journalism at that time. To them it was yellow kid journalism, after Outcault's Yellow Kid comic strips, about which I've previously written (see New York Sunday comics in the 90s & aughts).

[3] A contemporary account describes the whole process in considerable detail: Modern industrial progress by Charles Henry Cochrane (J.B. Lippincott company, 1904). I've outlined the method of making newspaper text in a previous blog post: Newspaper Story.

[4] In practice, more than three printing plates could be used. There might be one for black and grey tones and another for brown. Where faithfulness to the original picture was important, such as with high quality fine art reproductions, more plates would be added for different prominent tones in the original.

[5] "Photo-Lithography" in The chemistry of light and photography: in its application to art, science, and industry by Hermann Wilhelm Vogel (London, Henry S. King & Co., 1875

[6] See "Halftones" in the same source, and:

HALF-TONE ILLUSTRATION OVERLAYING

By "half-tone," in so far as this relates to printing plates made by the photo-mechanical process, is meant all engravings, pictorial and otherwise, which have their grays or lighter tones produced or enhanced by mesh formations over the face of the engraving, whether these be conveyed through a "dotted" or "lined" glass screen — the usual mechanical manner of producing half-tone effects on this character of printing plate.

-- The Inland and American printer and lithographer (Maclean-Hunter Pub. Co., 1895)