Journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson

April 9, 1840

We walked this afternoon to Edmund Hosmer's and Walden Pond. The South wind blew and filled will bland and warm light the dry sunny woods. The last year's leaves flew like birds through the air. As I sat on the bank of the Drop, or God's Pond, and saw the amplitude of the little water, what space, what verge, the little scudding fleets of ripples found to scatter and spread from side to side and take so much time to cross the pond, and saw how the water seemed made for the wind, and the wind for the water, dear playfellows for each other, -- I said to my companion, I declare this world is so beautiful that I can hardly believe it exists. At Walden Pond the waves were larger and the whole lake in pretty uproar. Jones Very said, 'See how each wave rises from the midst with an original force at the same time that it partakes the general movement!'

This is one of Emerson's more poetic entries. No longer a preacher, in April 1840 Emerson earned his living by giving lectures, supplemented by a small inheritance from the estate of his late wife. He helped found

The Dial this year and was building his first book of essays. His daughter, Ellen, was just a bit more than a year old.

A few years later he would purchase land on Walden Pond and help his friend, Henry Thoreau, build a cabin on it.

Jones Very was one of the more eccentric of Emerson's

clan of eccentric friends.

The journal entry continues with an odd anecdote about Very:

He [Very] said that he went to Cambridge, and found his brother reading Livy. 'I asked him if the Romans were masters of the world? My brother said they had been: I told him they were still. Then I went into the room of a senior who lived opposite, and found him writing a theme. I asked him what was his subject? And he said, Cicero's Vanity. I asked him if the Romans were masters of the world? He replied they had been: I told him they were still. This was in the garret of Mr. Ware's house. Then I went down into Mr. Ware's study, and found him reading Bishop Butler, and I asked him if the Romans were masters of the world? He said they had been: I told him they were still.'

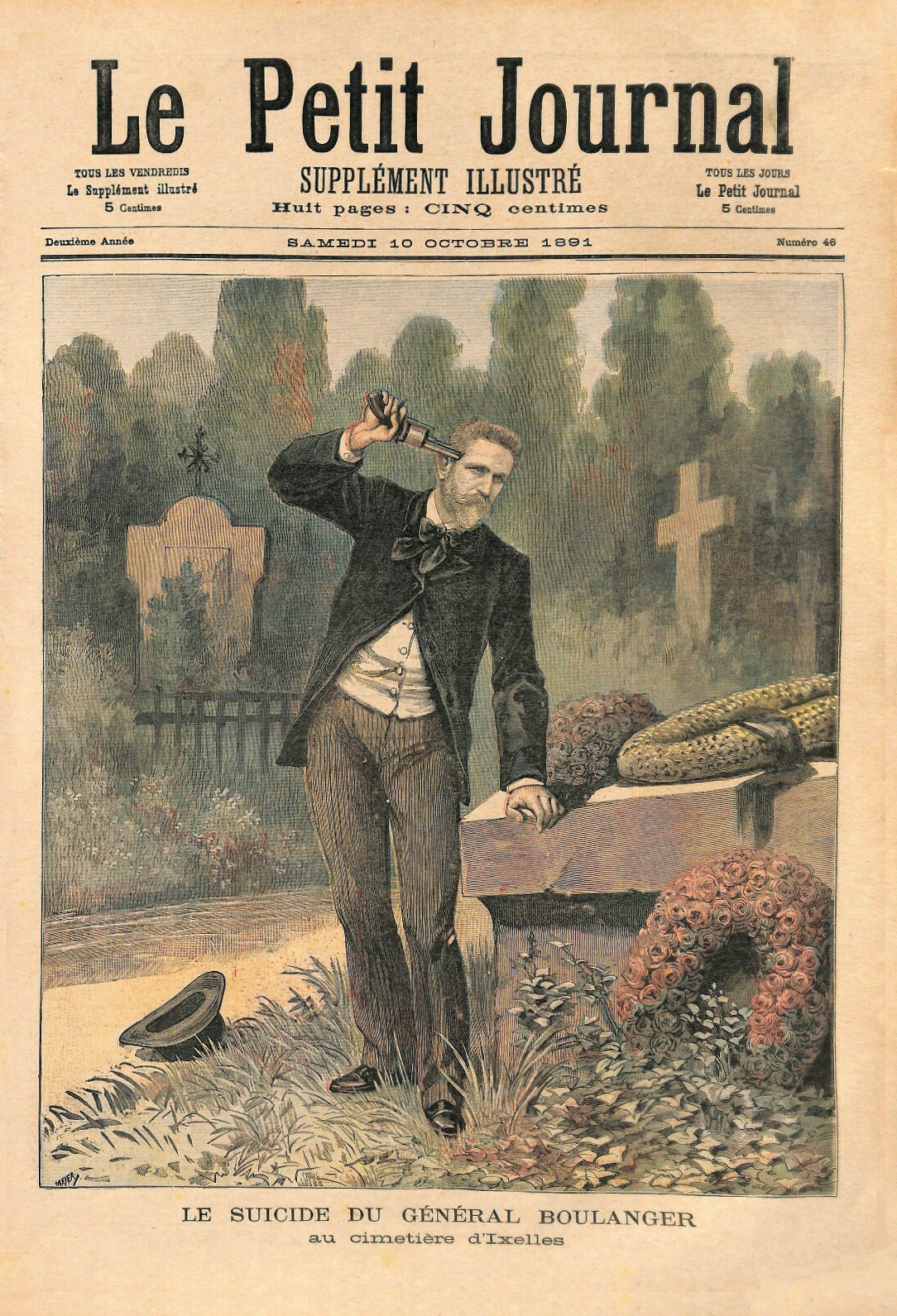

About Romans that are still masters of the world, there's, coincidentally, an op-ed piece in today's Washington Post on the American Imperium as echo of the Roman.

'Rome' Isn't Just Television. It's Us, by Nicholas Meyer (Sunday, April 8, 2007; Page B02). In this piece about the HBO series,

Rome, The author reminds us of the Roman connections that were strongly felt by America's Founding Fathers and draws some parallels between the history of the Roman Republic and ours. In this connection, he says, "As, one by one, our civil liberties and republican traditions are erased, as our adventures in foreign lands end in tragedy, we can see in "Rome" a mirror, as it were, held up to ourselves."

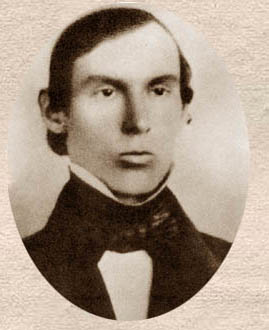

{Jones Very.

Source. This is a photo on the Jones Very page on American Transcendentalism web site.}

.jpg)

.jpg)