At one point he lists some of the decisions photographers made back in the era of silver-gelatin film photography. These include the selection of camera and film format, the choice of lens focal length, choice of shutter speed and aperture; they include what time of day to shoot and under what lighting conditions, what subject is chosen, how a human subject is posed, how a shot is framed, and what position the lens is given with respect to the subject; and they include decisions about whether the image is cropped after developing and whether it is dodged or retouched when printing. There are so many factors that affect the impact of a photograph that a small alteration of objects can seem a small thing to a photographer.

He also points out that the two men were acting as government employees — they worked under Roy Stryker in the Information Division of the Farm Security Administration and, while Stryker gave them lots of help and information, he didn't caution them about maintaining documentary purity.

Moving beyond the question of manipulated images, Morris asks about the editorial selection of images for publication. The photographers would take tens, even hundreds of shots at a location but only a few would be distributed to news media by the FSA (or in the case of Walker Evans, also produced in a book: James Agee's Let Us Now Praise Famous Men).

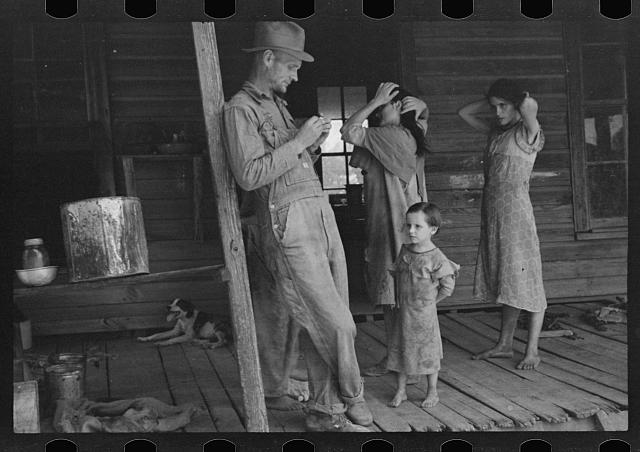

An online history course — History Matters — addresses this issue in a segment called Posing for the Camera Walker Evans Photographs Alabama Sharecroppers.* It gives three images from a set Evans made of Floyd Burroughs, a Southern sharecropper and his family, and discusses the likely rationale for selection of only one for the Agee book. The one selected has become iconic, that is to say one of the most widely-known and -reproduced of the FSA photographs.

As it happens, one of the two remaining (unchosen) examples in the online course has also become widely known. It shows the Burroughs family in Sunday clothes as a group portrait by the side of their house on a bright sunny morning.

Morris reproduces this image in one of the "Inappropriate Alarm Clock" posts in an interview with William Stott, author of Documentary Expression and Thirties America. In response to Morris' questions, Stott says he saw the photo in an exhibition of Evans' photographs at the Museum of Modern Art in 1971. It impressed him because it shows a certain amount of pride, a certain amount of contentment. It showed Burroughs, in Morris' words, "radiating life and virility and joy." This, he said, counterbalanced the images in Agee's book of people beaten down and at the end of their strength. Stott is saying, in effect, that the Agee book should have given all three of the photos in the online course, not just the one, famous as it is.

Morris reproduces this image in one of the "Inappropriate Alarm Clock" posts in an interview with William Stott, author of Documentary Expression and Thirties America. In response to Morris' questions, Stott says he saw the photo in an exhibition of Evans' photographs at the Museum of Modern Art in 1971. It impressed him because it shows a certain amount of pride, a certain amount of contentment. It showed Burroughs, in Morris' words, "radiating life and virility and joy." This, he said, counterbalanced the images in Agee's book of people beaten down and at the end of their strength. Stott is saying, in effect, that the Agee book should have given all three of the photos in the online course, not just the one, famous as it is.There's more to be said about this family portrait. It's found not only in MOMA collections, but also at George Eastman House where it is fully described: Burroughs Family, Hale County, Alabama. However, although it is certainly also to be found in the LC collections of Evans' photographs, it is not easily found there (I couldn't find it in a couple hours of searching).

All the discussion about the FSA photos is interesting — and there's a great deal more of it. I agree with Stott that a balanced cross section of photos is more interesting than individual ones selected for the the compelling stories they appear to tell.

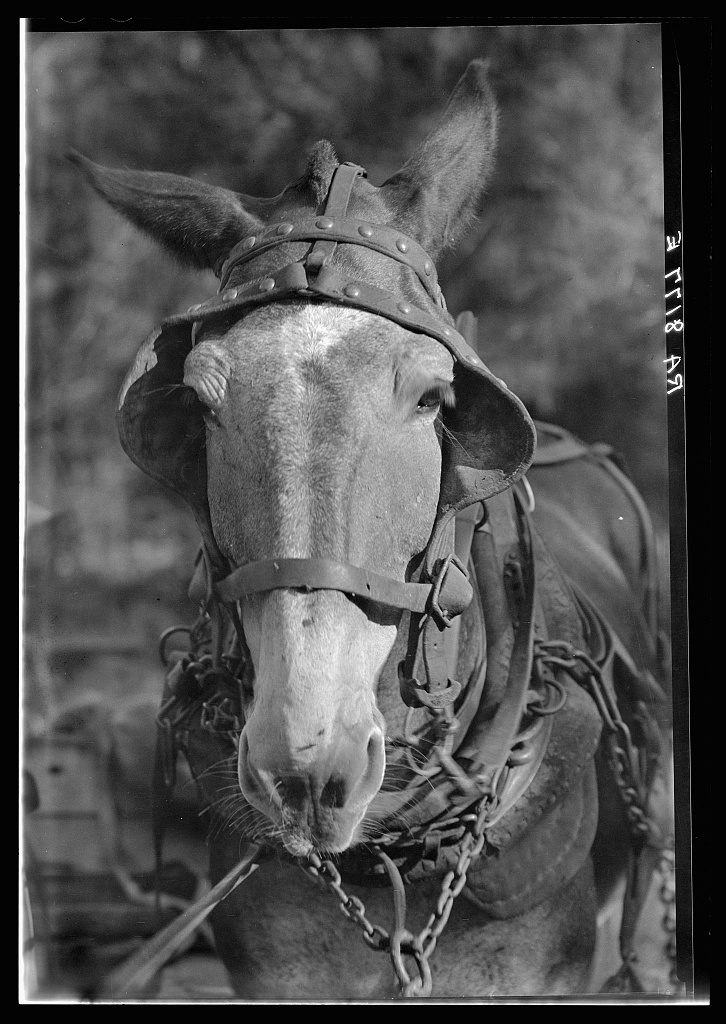

So, here are some other of Walker Evans' photographs that I found while searching for that one. Unless otherwise noted, all were taken in the Summer of 1936. All have captions supplied by LC staff from information supplied by FSA. All come from FSA Collection in the Prints and Photos Division of the Library of Congress. Click image to view full size.

----------------------------

Note:

*The course was created by the American Social History Project / Center for Media and Learning (Graduate Center, CUNY) and the Center for History and New Media (George Mason University).

No comments:

Post a Comment