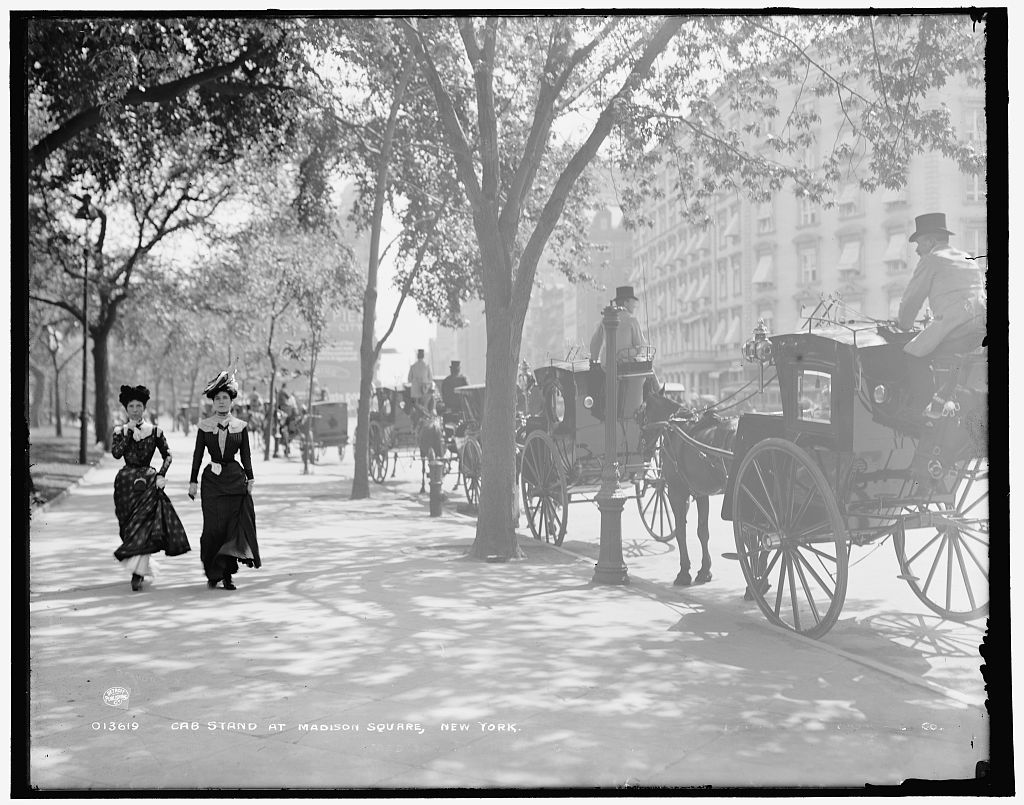

The other day, when I found this image of these fashionable ladies in this fashionable park, I also found a predecessor, the fictional "Miss Flora McFlimsey of Madison Square" whose complaint is that she has "nothing to wear."

This drawing of Miss Flora appears on the title sheet of a poem, Nothing To Wear. An Episode Of City Life, which first saw life in the issue of Harper's Weekly for February 7, 1857. Its author, William Allen Butler, satirizes the shallow life of a spoiled young lady who had a closet full of clothes but, she tells us, nothing to wear.1

Flora McFlimsey soon became a celebrity and by 1863, when this next illustration appeared, her elegance and self-regard are both readily apparent.

The poem begins:

Miss Flora McFlimsey, of Madison Square,

Has made three separate journeys to Paris,

And her father assures me, each time she was there,

That she and her friend Mrs. Harris

(Not the lady whose name is so famous in history,

But plain Mrs. H., without romance or mystery)2

Spent six consecutive weeks without stopping

In one continuous round of shopping, —

Shopping alone, and shopping together,

At all hours of the day, and in all sorts of weather, —

For all manner of things that a woman can put

On the crown of her head or the sole of her foot,

Or wrap round her shoulders, or fit round her waist,

Or that can be sewed on, or pinned on, or laced,

Or tied on with a string, or stitched on with a bow,

In front or behind, above or below;

For bonnets, mantillas, capes, collars, and shawls;

Dresses for breakfasts and dinners and balls;

Dresses to sit in and stand in and walk in;

Dresses to dance in and flirt in and talk in;

Dresses in which to do nothing at all;

Dresses for winter, spring, summer, and fall;

All of them different in color and pattern,

Silk, muslin, and lace, crape, velvet, and satin,

Brocade, and broadcloth, and other material,

Quite as expensive and much more ethereal;

In short, for all things that could ever be thought of,

Or milliner, modiste, or tradesman be bought of,

From ten-thousand-francs robes to twenty-sous frills;

In all quarters of Paris, and to every store,

While McFlimsey in vain stormed, scolded, and swore,

They footed the streets, and he footed the bills.

Here are some illustrated excerpts from the rest of the poem:3

I should mention just here, that out of Miss Flora's

Two hundred and fifty or sixty adorers,

I had just been selected as he who should throw all

The rest in the shade, by the gracious bestowal

On myself, after twenty or thirty rejections,

Of those fossil remains which she called "her affections,"

And that rather decayed, but well-known work of art,

Which Miss Flora persisted in styling "her heart."

So we were engaged. Our troth had been plighted,

Not by moonbeam or starbeam, by fountain or grove,

But in a front parlor, most brilliantly lighted,

Beneath the gas-fixtures we whispered our love.

Without any romance, or raptures, or sighs,

Without any tears in Miss Flora's blue eyes,

Or blushes, or transports, or such silly actions,

It was one of the quietest business transactions,

With a very small sprinkling of sentiment, if any,

And a very large diamond imported by Tiffany.

On her virginal lips while I printed a kiss.

She exclaimed, as a sort of parenthesis,

And by way of putting me quite at my ease,

"You know, I'm to polka as much as I please,

And flirt when I like—now stop, don't you speak —

And you must not come here more than twice in the week,

Or talk to me either at party or ball,

But always be ready to come when I call

So don't prose to me about duty and stuff.

If we don't break this off, there will be time enough

For that sort of thing; but the bargain must be

That, as long as I choose, I am perfectly free,

For this is a sort of engagement, you see,

Which is binding on you but not binding on me."

I found her, — as ladies are apt to be found,

When the time intervening between the first sound

Of the bell and the visitor's entry is shorter

Than usual, — I found — I won't say, I caught her, —

Intent on the pier-glass, undoubtedly meaning

To see if perhaps it didn't need cleaning.

She turned as I entered, — "Why, Harry, you sinner,

I thought that you went to the Flashers' to dinner!"

"So I did," I replied; "but the dinner is swallowed

And digested, I trust, for 'tis now nine and more,

So being relieved from that duty, I followed

Inclination, which led me, you see, to your door;

And now will your ladyship so condescend

As just to inform me if you intend

Your beauty and graces and presence to lend

(All of which, when I own, I hope no one will borrow)

To the Stuckups', whose party, you know, is to-morrow?"

The fair Flora looked up with a pitiful air,

And answered quite promptly, "Why, Harry, mon cher,

I should like above all things to go with you there;

But really and truly — I've nothing to wear."

"Then wear," I exclaimed, in a tone which quite crushed

Opposition, "that gorgeous toilette which you sported

In Paris last spring, at the grand presentation,

When you quite turned the head of the head of the nation;

And by all the grand court were so very much courted."

The end of the nose was portentously tipped up,

And both the bright eyes shot forth in dignation,

As she burst upon me with the fierce exclamation,

"I have worn it three times at the least calculation,

And that and the most of my dresses are ripped up!"

Here I ripped out something, perhaps rather rash,

Quite innocent, though; but, to use an expression

More striking than classic, it "settled my hash,"

And proved very soon the last act of our session.

"Fiddlesticks, it is, sir? I wonder the ceiling

Doesn't fall down and crush you — oh! you men have no feeling;

You selfish, unnatural, illiberal creatures,

Who set yourselves up as patterns and preachers,

Your silly pretense, — why, what a mere guess it is!

Pray, what do you know of a woman's necessities!

I have told you and shown you I've nothing to wear,

And it's perfectly plain you not only don't care,

But you do not believe me" (here the nose went still higher).

"I suppose, if you dared, you would call me a liar.

Our engagement is ended, sir — yes, on the spot;

You're a brute and a monster, and—I don't know what."

Well, I felt for the lady, and felt for my hat, too,

Improvised on the crown of the latter a tattoo,

In lieu of expressing the feelings which lay

Quite too deep for words, as Wordsworth would say;

Then, without going through the form of a bow,

Found myself in the entry — I hardly knew how, —

On doorstep and sidewalk, past lamp-post and square,

At home and up stairs, in my own easy-chair;

Poked my feet into slippers, my fire into blaze,

And said to myself, as I lit my cigar,

Supposing a man had the wealth of the Czar

Of the Russias to boot, for the rest of his days,

On the whole, do you think he would have much to spare,

If he married a woman with nothing to wear?"

Since that night, taking pains that it should not be bruited

Abroad in society, I've instituted

A course of inquiry, extensive and thorough,

On this vital subject, and find, to my horror,

That the fair Flora's case is by no means surprising,

But that there exists the greatest distress

In our female community, solely arising

From this unsupplied destitution of dress,

Whose unfortunate victims are filling the air

With the pitiful wail of "Nothing to wear."

Researches in some of the "Upper Ten" districts

Reveal the most painful and startling statistics,

Of which let me mention only a few:

In one single house, on Fifth Avenue,

Three young ladies were found, all below twenty-two,

Who have been three whole weeks without anything new

But the choicest assortment of French sleeves and collars

Ever sent out from Paris, worth thousands of dollars,

And all as to style most recherche and rare,

The want of which leaves her with nothing to wear,

And renders her life so drear and dyspeptic

That she's quite a recluse, and almost a sceptic;

For she touchingly says that this sort of grief

Cannot find in Religion the slightest relief,

And Philosophy has not a maxim to spare

For the victims of such overwhelming despair.

But the saddest by far of all these sad features

Is the cruelty practised upon the poor creatures

By husbands and fathers, real Bluebeards and Timons,

Who resist the most touching appeals made for diamonds

By their wives and their daughters, and leave them for days

Unsupplied with new jewelry, fans, or bouquets,

Even laugh at their miseries whenever they have a chance,

And deride their demands as useless extravagance;

One case of a bride was brought to my view,

Too sad for belief, but, alas! 'twas too true,

Whose husband refused, as savage as Charon,

To permit her to take more than ten trunks to Sharon.

The consequence was, that when she got there,

At the end of three weeks she had nothing to wear,

And when she proposed to finish the season

At Newport, the monster refused out and out,

For his infamous conduct alleging no reason,

Except that the waters were good for his gout.

Such treatment as this was too shocking, of course,

And proceedings are now going on for divorce.

Oh ladies, dear ladies, the next sunny day---------

Please trundle your hoops just out of Broadway,

From its whirl and its bustle, its fashion and pride,

And the temples of Trade which tower on each side,

To the alleys and lanes, where Misfortune and Guilt

Their children have gathered, their city have built;

Where Hunger and Vice, like twin beasts of prey,

Have hunted their victims to gloom and despair;

Raise the rich, dainty dress, and the fine broidered skirt,

Pick your delicate way through the dampness and dirt,

Grope through the dark dens, climb the rickety stair

To the garret, where wretches, the young and the old,

Half-starved, and half-naked, lie crouched from the cold.

See those skeleton limbs, those frost-bitten feet,

All bleeding and bruised by the stones of the street;

Hear the sharp cry of childhood, the deep groans that swell

From the poor dying creature who writhes on the floor,

Hear the curses that sound like the echoes of Hell,

As you sicken and shudder and fly from the door;

Then home to your wardrobes, and say, if you dare,—

Spoiled children of Fashion,—you've nothing to wear!

And oh, if perchance there should be a sphere

Where all is made right which so puzzles us here,

Where the glare and the glitter and tinsel of Time

Fade and die in the light of that region sublime,

Where the soul, disenchanted of flesh and of sense,

Unscreened by its trappings and shows and pretence,

Must be clothed for the life and the service above,

With purity, truth, faith, meekness, and love;

O daughters of Earth! foolish virgins, beware!

Lest in that upper realm you have nothing to wear!

The hoop-skirt fashions of the middle of the nineteenth century drew some good-natured ridicule from cartoonists as well as moralists and satirical poets. This appeared in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper at mid-century.

The contrast with earlier fashion was obvious even to those who approved of the change, as these 1857 cartoons from Harper's Weekly demonstrate.

A few other images of the fashions of the time:

-----------

See also:

Victorian Fashion- Dressing the Victorian Lady from the 1850s

The Mid Nineteenth Century

The lady's guide to perfect gentility, in manners, dress, and conversation ... also a useful instructor in letter writing by Emily Thornwell (Derby & Jackson, 1857)

1850s in fashion

Godey's Lady's Book illustrations from 1855-59

Dress of the 1850's

Madison Square Park

-------------

Notes:

1 Neither Miss Flora's picture nor Butler's name appeared in that February issue of Harper's Weekly. They are both together, as you see, on this reissue which appeared later the same year in Harper's sister magazine, the illustrated Monthly. William Allen Butler was a celebrated lawyer with a talent for humorous verse. The poem, which was an immediate success, appeared in book form before the year was out and appeared again repeatedly over the next few decades. As one source explains:

Butler, in his poem of "Nothing to Wear," made one of those hits which become immortal in literature. The inconsistency of a phrase so constantly heard in an age of extravagance, almost unexampled in history, give a point to the conventional miseries of Miss Flora McFlimsey, that drew laughter from all, even from the thousand copies of the great prototype. Few of our readers can fail to remember among the artistic beauties that covered the walls of the National Academy of Design, at its last exhibition, a charming "Nothing to Wear," from the pencil of Louis Lang. A painter of merit, and rapidly rising in the public esteem, he needs but time to assume a high rank among the artists of America. We present our readers with a copy of the beautiful piece to which we have alluded.

The figure of Miss Flora McFlimsey, amid the luxury of her boudoir, where all breathes of wealth, ancestral pride, and voluptuous ease, is charmingly conceived, and the chagrin on her fair brow, as gazing on her rich dress she is forced to confess that she has nothing to wear, is such a picture of real sorrow, that properly understood and appreciated, as it will doubtless be by our readers, it must move the sympathetic even to tears.

-- quoted from Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 1863

2 The Mrs. H. of romance and mystery was probably Sairey Gamp's imaginary friend in The life and adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit by Charles Dickens.

"Sairey" Gamp. She was a fat old woman, with a red face, a husky voice and a moist eye, which often turned up so as to show only the white. Wherever she went she carried a faded umbrella with a round white patch on top, and she always smelled of whisky. Mrs. Gamp was fond of talking of a certain "Mrs. Harris," whom she spoke of as a dear friend, but whom nobody else had ever seen. When she wanted to say something nice of herself she would put it in the mouth of Mrs. Harris. She was always quoting, "I says to Mrs. Harris," or "Mrs. Harris says to me." People used to say there was no such person at all, but this never failed to make Mrs. Gamp very angry. ... "Bother Mrs Harris," said Betsey Prig, "I don't believe there's no such person."

3 The illustrator is Augustus Hoppin and the pictures appear in Nothing to wear: an episode of city life: from Harpers weekly by William Allen Butler, illustrated by Augustus Hoppin (J. Bradburn, 1862)

No comments:

Post a Comment