I've probably now read nine tenths of the Orwell that's available in print — quite a bit of reading — and am currently finishing vol. 2 of the collected essays, journalism, and letters. It's full of his distaste for the left-wing intellectuals of his time whom he thought to lack consistency, conscience, or common decency. He accused them of indulging in opposition for opposition's sake and of willful blindness to the horrendous wrongs done by the Soviet regime they idolized. It's also full of his visceral dislike the class system and the stubborn stupidities of the upper-class social and political establishment. He believed that the events of the 1930s and the years of World War II would bring about a peaceful revolution, one that would establish a humane socialism and what later would come to be called the welfare state.

He condemned wrong-headed beliefs but not the people who held them. He wrote public criticisms of the writings of his friends, but nurtured those friendships nonetheless. He deplored propaganda, but -- without compromising his beliefs -- worked side by side with propagandists at the BBC through much of WWII. He carefully distinguished between the politics and the literary worth of men like T.S. Eliot, Rudyard Kipling, and Mark Twain. He was openly critical of writings by men whose beliefs he shared. He was passionate in believing that all the resources of the nation needed to be harnessed in order to overcome the aggression of Nazi Germany and other totalitarian states. Yet he could write a review of Hitler's Mein Kampf in which he empathized with those who looked up to him.*. He did not romanticize or idolize working class people as did many of his contemporaries; did not claim for them greater acuity than they, on the whole, possessed; and — far from envisioning a dictatorship of the proletariat — believed that the gradual merging of the middle and working classes was not a bad thing.

An article in last Sunday's Times (of London) speaks to one side of his complex nature: George Orwell's son speaks for the first time about his father, John Carey talks to George Orwell's son (Richard Blair, The Sunday Times, March 15, 2009).

This extract from his diary shows the importance to him of factual accuracy, freedom from bombast, and plainspokeness. But, more than that, it shows a side of himself that he shared with many of his compatriots: a composure, self-confidence, and pluck.

War-time Diary: 8 April 1941People mentioned in this entry:

Have just read The Battle of Britain, the MOI's best best-seller (there was so great a run on it that copies were unprocurable for some days). ... I suppose it is not as bad as it might be, but seeing that it is being translated into many languages and will undoubtedly be read all over the world — it is the first official account, at any rate in English, of the first great air battle in history — it is a pity that they did not have the sense to avoid the propagandist note altogether. ... For the sake of the bit of cheer-up that this pamphlet will accomplish in England, they throw away the chance of producing something that would be accepted all over the world as a standard authority and used to counteract German lies.

But what chiefly impresses me when reading The Battle of Britain and looking up the corresponding dates in this diary, is the way in which "epic" events never seem very important at the time. Actually I have a number of vivid memories of the day the Germans broke through and fired the docks (I think it must have been the 7th September), but mostly of trivial things. ... Sheltering in a doorway in Piccadilly from falling shrapnel, just as one might shelter from a cloudburst. ... Then sitting in Connolly's top-floor flat and watching the enormous fires beyond St Paul's, and the great plume of smoke from an oil drum somewhere down the river, and Hugh Slater sitting in the window and saying, "It's just like Madrid — quite nostalgic." The only person suitably impressed was Connolly, who took us up to the roof and, after gazing for some time at the fires, said "It's the end of capitalism. It's a judgement on us." I didn't feel this to be so, but was chiefly struck by the size and beauty of the flames. That night I was woken up by the explosions and actually went out into the street see if the fires were still alight — as a matter of fact it was almost as bright as day, even in the N.W. quarter — but still didn't feel as though any important historical event were happening. Afterwards, when the attempt to conquer England by air bombardment had evidently been abandoned, I said to Fyvel, "That was Trafalgar. Now there's Austerliz," but I hadn't seen this analogy at the time. ...

Cyril Connolly school friend, New Statesman, Horizon

Humphrey Slater, painter, author, and ex-Communist. Involved in anti-Nazi politics in Berlin in the early 'thirties. Went to Spain as political journalist and fought for the Republicans 1936-8, becoming Chief of Operations in the International Brigade. Helped Tom Wintringham to found Osterley Park training centre for the Home Guard in 1940. Edited Polemic (1945-7) to which Orwell contributed several pieces. (note in Collected Essays..)

T.R. (Tosco) Fyvel, born in Switzerland in 1907 and educated in England, he was, like Orwell, a writer, journalist and broadcaster. The two became friends in 1940.

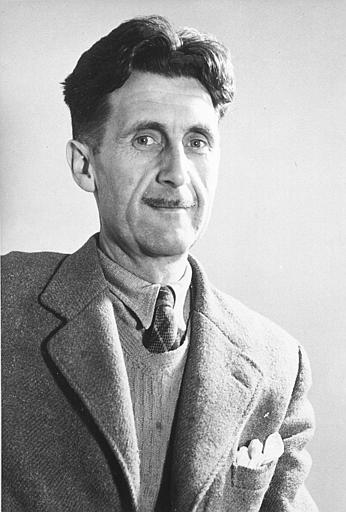

This interesting image needs some explaining. It comes from the home page of the British Security Service, MI5, and it shows Orwell's war years passport photo. The Security Service had a file on him, as the page explains. It's hardly credible that the police thought him a Communist, unless they made no distinction among Communists, socialists, anarchists, and left-liberals. Orwell believed that many in power were simply ignorant; that is, not just uninformed, but willfully so: stupid.

File ref KV 2/2699

This slim Security Service file on journalist and author Eric Blair, alias George Orwell, shows that while his left-wing views attracted the Service's attention, no action was taken against him. It is clear, however, that he continued to arouse suspicions, particularly with the police, that he might be a Communist. The file reveals that the Service took action to counter these views.

The file essentially consists of reports of Orwell's activities between 1929 and his death in 1952. It gives some insight into Orwell's financial position while in Paris and includes a 1929 MI6 report to the Special Branch on his activities there, and various subsequent Special Branch reports. One of these by police Sergeant Ewing, from January 1942 (serial 7a), asserts that: "This man has advanced Communist views, and several of his Indian friends say that they have often seen him at Communist meetings. He dresses in a bohemian fashion both at his office and in his leisure hours." A Service officer rang Ewing's Inspector to challenge this view (minute 9). Wartime enquiries as to Orwell and his wife's suitability for employment as a journalist and with the Ministry of Food were all approved. It is of some interest to note the part Orwell's answers to a published Left magazine survey had in convincing the Service that Orwell should not be considered a Communist. The file includes a copy of Orwell's passport papers and original passport photographs.

The Service was inadequately prepared for the massive increase in work that came with the onset of war. It had far too few staff to deal with its new responsibilities. At the end of 1938, the Service had only 30 officers and another 103 secretaries and registry staff.

These problems meant that, when war was declared, a flood of reports, vetting requests and enquiries overwhelmed the Security Service. During the second quarter of 1940, the Service received an average of 8,200 vetting requests each week. The Service also had to contend with fears of a "Fifth Column" of Nazi sympathizers in Britain working to prepare the ground for a German invasion. This resulted in thousands of reports of suspected enemy activity, each of which had to be investigated.

The problem rapidly worsened with the introduction of internment (imprisonment without trial). Within the first six months of the war, 64,000 citizens of Germany, Austria and Italy resident in the UK had to undergo security interviews to confirm that they were "friendly aliens". In addition, suspected British Nazi sympathisers such as Sir Oswald Mosley were imprisoned to guard against the threat of domestic subversion.

The security file says: "He dresses in a bohemian fashion both at his office and in his leisure hours." His friend Fyvel described him as "a very tall, thin man with a long, thin, haggard face, with deep-set blue eyes, a poor, small mousatche and deep lines etched in grooves down his face."

Note:

*From Review of Mein Kampf: "I should like to put it on record that I have never been able to dislike Hitler. Ever since he came to power — till then, like nearly everyone, I had been deceived into thinking that he did not matter — I have reflected that I would certainly kill him if I could get within reach of him, but that I could feel no personal animosity. The fact is that there is something deeply appealing about him." Hitler's photograph shows "a pathetic, dog-like face, the face of a man suffering under intolerable wrongs. In a rather more manly way it reproduces the expression of innumerable pictures of Christ crucified."

Some sources:

The collected essays, journalism, and letters of George Orwell, edited by Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus (New York, Harcourt, Brace & World, 1968)

The battle of Britain, August-October 1940. An Air ministry record of the great days from 8th August- 31st October, 1940., by Great Britain. Air Ministry. (Great Britain. Ministry of Information, London, H.M. Stationery Office, 1941). Alternative citation.

No comments:

Post a Comment