April [day not given].

The British Museum holds the relics of ancient art, and the relics of ancient nature, in adjacent chambers. It is alike impossible to reanimate either.

The arrangement of the antique remains is surprisingly imperfect and careless, without order, or skilful disposition, or names or numbers. A warehouse of old marbles. People go to the Elgin chamber many times, and at last the beauty of the whole comes to them at once, like music. The figures sit like gods in heaven.

Coventry Patmore's remark was, that to come out of the other room to this was from a roomful of snobs to a room full of gentlemen.

There are 420,000 volumes in the library, as Mr. Panizzi assured me, and fifty or sixty thousand manuscripts. In the Bodleian Library probably not more than 120,000 books. Five libraries have the right to a copy of every book that is printed: this, the Bodleian, the Advocates' at Edinburgh, the Dublin University(?), and Trinity College, Cambridge(?). The King's Library at Paris is much larger than this — 1,500,000, said Colman. Here the line of shelves runs twelve miles. It is impossible to read from the glut of books. I looked at some engravings in the print-room with Mr. Patmore, who is connected with this Library.

Ah! there is a nation completely appointed, and perhaps conveniently small.

St. Paul's is, as I remember it, a very handsome, noble architectural exploit, but singularly unaffecting. When I formerly came to it from the Italian cathedrals, I said, "Well, here is New York." It seems the best of show-buildings, a fine British vaunt, but there is no moral interest attached to it.

It is certain that more people speak English correctly in the United States than in Britain.

The Government offers free passage to Australia for twenty-five thousand women. In Australia are six men to one woman. Miss Coutts has established a school to teach poor girls, taken out of the street, how to read and write and make a pudding and be a colonist's wife. They do very well so long as they are there, but when it comes to embarking for Australia they prefer to go back to the London street, though in these times it would seem as if they must eat the pavement. Such is the absurd love of home of the English race, said Dickens.

--------------April 15.

At the British Museum with the Bancrofts under the guidance of Sir Charles Fellows. Lycian Art. The triumphal Temple plagiarism of the Parthenon. Exact truth and fitness of every particular of Greek work. There are ten statues because ten cities sent aid out of thirteen. Every statue stands on an emblem, as crab, dove, snake, etc., which the coins now show to be the arms of the ten cities. The gods are at the eastern end. The friezes describe accurately the siege of the city.

The reconstruction of the Temple, like that of the Dinornis, the most beautiful work of archaic science. History, geology, chemistry, and good sense. The temple itself imitates in stone the old carpentry of the country still visible in the huts of the peasantry, and is an ark. The women wear the same ornaments, the boys have the same tuft of hair.

Illustration of Homer and Herodotus. England holds these things for mankind and holds them well. Conservative, she is conservator.

Owen said he fell in with a sentinel in crossing the French frontier, who cried out, "Who are you?" Mr. Arnott said he should have replied, "The creature of circumstances."

One power streams into all natures. Mind is vegetable, and grows, thought out of thought, as joint out of joint in corn. Mind is chemical, and shows all the affinities and repulsions of chemistry, and works by presence. . . .

Mind knows the way because it has trod it before. Knowledge is becoming of that thing. Somewhere, sometime, some eternity, we have played this game before. Go through the British Museum and we are full of occult sympathies. I was azote.

It is a little fearful to see with what genius some people take to hunting; what knowledge they still have of the creature they hunt; how lately they were his organic enemy; and the physiognomies in the street have their type in woods.[1] As in the British Museum one feels his family ties, so in astronomy not less; little men copernicise.

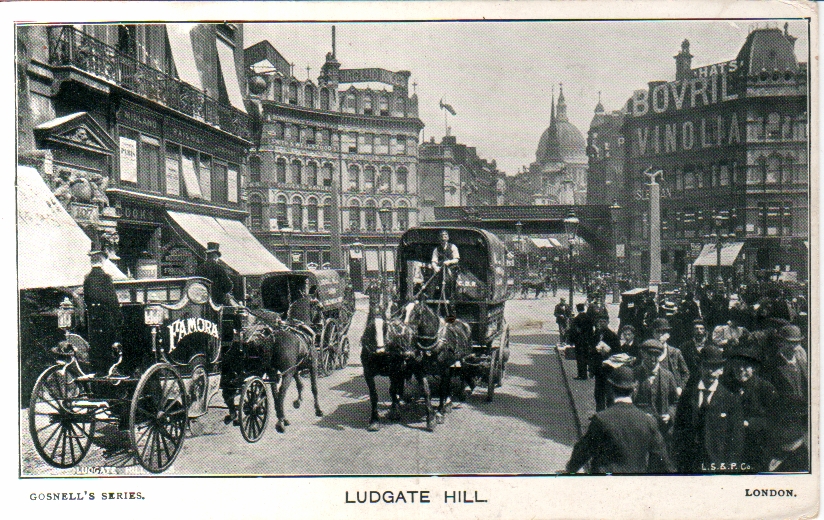

Ludgate still keeps the hoary memory of Lud's town. Lud, son of Beli, is represented in the romantic chronicles as the elder brother of Cassivellaunus who fought with Julius Caesar.

Among the trades of despair is the searching the filth of the sewers for rings, shillings, teaspoons, etc., which have been washed out of the sinks. These sewers are so large that you can go underground great distances. Mr. Colman saw a man coming out of the ground with a bunch of candles. "Pray, sir, where did you come from?" "Oh, I've been seven miles," the man replied. They say that Chadwick[2] rode all under London on a little brown pony.

I wonder the young people are so eager to see Carlyle. It is like being hot to see the Mathematical or the Greek professor, before you have got your lesson. They fancy it needs only clean shirt and palaver. If the genius is true, it needs genius.

The Englishman is finished like a sea-shell. After the spires and volutes are all formed, or with the formation, the hard enamel varnishes every part. Pope, Swift, Jonson, Gibbon, Goldsmith, Gray. It seems an indemnity to the Briton for his precocious maturity. He has no generous daring in this age. The Platonism died in the Elizabethan. He is shut up in French limits. . . .

But Birmingham comes in, and says, "Never mind, I have some patent lustre that defies criticism." Moore made his whole fabric of the lustre: as we cover houses with a shell of inconsumable paint.

--------------April 19.

At Kew Gardens, which enclose in all more than six hundred acres, Sir William Hooker showed us his new glass palm-house . . . which cost .£40,000. The whole garden an admirable work of English power and taste. Good as Oxford or the British Museum. No expense spared, all climates searched. The Echino cactus Visnasa, which is a thousand years old, cost many hundred pounds to transport it from the mountains in Mexico to the sea. Here was tea growing, green and black ; here was clove, cinnamon, chocolate, lotus, caoutchouc, gutta-percha, kava, upas, baobab, orotava, the papaw, which makes tough meat tender, \hegraphtophyllumpictum or caricature-plant, on whose leaves were several good Punch portraits visible to me (lately, there was one so good of Lord Brougham appeared, that all men admire); the ivory nut; the Strelitzia Regina, named for Queen Charlotte, one of the gayest flowers in nature; it looked like a bird, and all but sung; the papyrus; the banian; a whole greenhouse or "stove" full of wonderful orchises, which are the rage of England now.

Sydney Smith said of Whewell, that Science was his forte and Omniscience was his foible.

Carlyle thought the clubs remarkable signs of the times. That union was no longer sought, but only the association of men who would not offend one another. There was nothing to do, but they could eat better.

He said, There are about 70,000 of these people who make what is called "society." Of course, they do not need to make any acquaintance with new people like Americans.

Plato [he found] very unsatisfactory reading, very tedious. The use of intellect not to know that it was there, but to do something with it.

Happy is he who looks only into his work to know if it will succeed, never into the times or the public opinion; and who writes from the love of imparting certain thoughts and not from the necessity of sale — who writes always to the unknown friend.

--------------April 25.

Carlyle. Dined with John Forster, Esq., at Lincoln's Inn Fields, and found Carlyle and Dickens, and young Pringle. Forster, who has an obstreperous cordiality, received Carlyle with loud salutation,"My Prophet!" Forster called Carlyle's passion, "musket-worship." There were only gentlemen present and the conversation turned on the shameful lewdness of the London streets at night. "I hear it," he said, "I hear whoredom in the House of Commons. Disraeli betrays whoredom, and the whole House of Commons universal incontinence, in every word they say." I said that when I came to Liverpool, I inquired whether the prostitution was always as gross in that city as it then appeared, for to me it seemed to betoken a fatal rottenness in the state, and I saw not how any boy could grow up safe. But I had been told it was not worse nor better for years. Carlyle and Dickens replied that chastity in the male sex was as good as gone in our times; and in England was so rare that they could name all the exceptions. Carlyle evidently believed that the same things were true in America. He had heard this and that of New York, etc. I assured them that it was not so with us; that, for the most part, young men of good standing and good education, with us, go virgins to their nuptial bed, as truly as their brides. Dickens replied that incontinence is so much the rule in England that if his own son were particularly chaste, he should be alarmed on his account, as if he could not be in good health. "Leigh Hunt," he said, "thought it indifferent."

Carlyle is no idealist in opinions, but a protectionist in political economy, aristocrat in politics, epicure in diet, goes for murder, money, punishment by death, slavery, and all the pretty abominations, tempering them with epigrams. His seal holds a griffin with the word, Humilitate. He is a covenanter-philosophe and a sansculotte-aristocrat.[3] . . .

Yet it must be said of Carlyle that he has the kleins tads lie h traits of an islander and a Scotchman, and believes more deeply in London than if he had been born under Bow Bells, and is pretty sure to reprimand with severity the rebellious instincts of the native of a vast continent which makes light of the British islands. He is an inspired Cockney.

(When I saw him, in 1848,[4] he was reading Wright's translation of some of Plato's Dialogues with displeasure. I was told by Clough, in 1852, that he has since changed his mind, and professes vast respect for Plato.)

Carlyle is Malleus Mediocritatis. He detects weakness on the instant in his companion, and touches it. ...

I fancy, too, that he does not care to see anybody whom he cannot eat, and reproduce tomorrow, in his pamphlet or pillory. Alcott was meat that he could not eat, and Margaret Fuller likewise, and he rejected them, at once.

He is the voice of London, a true Londoner with no sweet country breath in him, and the instigation of these new Pamphlets is the indignation of the night-walking in London streets. And 't is curious, the magnificence of his genius and the poverty of his aims. He draws his weapons from the skies, to fight for some wretched English property, or monopoly, or prejudice.

He looks for such an one as himself. He would willingly give way to you and listen, if you would declaim to him as he declaims to you. But he will not find such a mate. And a short, plain-dealing and a communication of results, as when Dalton and Dana met, and without speaking, scratched down on scraps of paper chemical formulas, surprising each other with authentic proof of a chemist, — that he does not care for.

-----------------

Notes by the editor of the Journals:

1. Some sentences of the above are printed in " Powers and Laws of Thought" (Natural History of Intellect, p. 22).

2 The engineer of the London water system.

3 A large part of what is written in the next pages of the Journal is printed in the " Carlyle," in Lectures and Biographical Sketches.

4 This paragraph, Mr. Emerson wrote into the Journal years later.

From the editor of Carlyle's letters:

TC, Emerson, Dickens, and Forster dined together, 25 April. Emerson wrote to his wife, 4 May, that he found Dickens “cordial and sensible. Carlyle dined there also, and it seemed the habit of the set to pet Carlyle a great deal, and draw out the mountainous mirth. The pictures which such people together give one of what is really going forward in private & in public life, are inestimable”.

In 1862 an English social investigator, Henry Mayhew, published a report on prostitution in London. It formed a part of the larger work, London Labour and the London Poor. Here are its contents:

- Introduction

- Seclusives, or those that live in private houses and apartments

- Degree of education amongst prostitutes Degree of instruction amongst prostitutes compared with the degree of instruction among women not prostitutes, arrested for breaking various laws (London). The city not included Degree of instruction amongst virtuous women brought up in the police courts for various offences during the years elapsing from 1837 1854 inclusive.

- The Convives

- Board lodgers

- Sailor's Women

- Soldiers' women The happy prostitute The sensitive, sentimental, weak-minded, impulsive, affectionate girl

- Thieves' women

- Park women, or those who frequent the parks at night and other retired places.

- The dependents of prostitutes Bawds Followers of dress-lodgers Keepers of accommodation houses Procuresses Pimps, panders and Fancy-men Bullies

- Clandestine prostitutes Female operatives Ballet-girls Maid-servants Ladies of Intrigue and Houses of Assignation

- Cohabitant prostitutes

- Narrative of a gay woman at the west end of the metropolis

Some sources:

Journals Of Ralph Waldo Emerson 1820-1872, with Annotations, edited by Edward Waldo Emerson and Waldo Emerson Forbes; Vol. VII, 1845-1848, (New York, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912)

The Correspondence of Thomas Carlyle and Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1834-1872, edited by Charles Eliot Norton (Houghton, Mifflin, 1896)

Mayhew's London Prostitutes:

London labour and the London poor, by Henry Mayhew (C. Griffin, 1864)

No comments:

Post a Comment