Still, as he wrote to his friend Elizabeth Hoar on this date, the English aristocracy had its attractions.

TO MISS HOAR.London, June 21, 1848.

Dear Elizabeth, — I have been sorry to let two, or it may be three, steamers go without a word to you since your last letter. But there was no choice. Now my literary duties in London and England are for this present ended, and one has leisure not only to be glad that one's sister is alive, but to say so. I believe you are very impatient of my impatience to come home, but my pleasure, like everybody's, is in my work, and I get many more good hours in a Concord week than in a London one. Then my atelier in all these years has gradually gathered a little sufficiency of tools and conveniences for me, and I have missed its apparatus continually in England. The rich Athenaeum (Club) library, yes, and the dismaying library of the British Museum could not vie with mine in convenience. And if my journeying has furnished me new materials, I only wanted my atelier the more. To be sure, it is our vice — mine, I mean — never to be well; and to make all our gains by this indisposition. So you will not take my wishings for any more serious calamity than the common lot. And yet you must be willing that I should desire to come home and see you and the rest. Dear thanks for all the true kindness your letter brings. How gladly I would bring you such pictures of my experiences here as you would bring me, if you had them! Sometimes I have the strongest wish for your daguerreotyping eyes and narrative eloquence, but I think never more than the day before yesterday. The Duchess of Sutherland sent for me to come to lunch with her at two o'clock, and she would show me Stafford House. Now you must know this eminent lady lives in the best house in the kingdom, the Queen's not excepted. I went, and was received with great courtesy by the Duchess, who is a fair, large woman, of good figure, with much dignity and sweetness, and the kindest manners. She was surrounded by company, and she presented me to the Duke of Argyle, her son-in-law, and to her sisters, the Ladies Howard. After we left the table we went through this magnificent palace, this young and friendly Duke of Argyle being my guide. He told me he had never seen so fine a banquet hall as the one we were entering; and galleries, saloons, and anterooms were all in the same regal proportions and richness, full everywhere with sculpture and painting. We found the Duchess in the gallery, and she showed me her most valued pictures. ... I asked her if she did not come on fine mornings to walk alone amidst these beautiful forms; which she professed she liked well to do. She took care to have every best thing pointed out to me, and invited me to come and see the gallery alone whenever I liked. I assure you in this little visit the two parts of Duchess and of palace were well and truly played. ... I have seen nothing so sumptuous as was all this. One would so gladly forget that there was anything else in England than these golden chambers and the high and gentle people who walk in them! May the grim Revolution with his iron hand — if come he must — come slowly and late to Stafford House, and deal softly with its inmates! . . . Your affectionate brother, Waldo.

On this day Emerson also wrote to his wife Lydian:

Dear Lydian,London, June 21.

We finished the Marylebone course last Saturday afternoon, to the great joy, doubt not, of all parties. It was a curious company that came to hear the Massachusetts Indian, and partly new, Carlyle says, at every lecture. Some of the company probably came to see others; for, besides our high Duchess of Sutherland and her sister, Lord Morpeth and the Duke of Argyle came, and other aristocratic people; and as there could be no prediction what might be said, and therefore what must be heard by them, and in the presence of Carlyle and Monckton Milnes, etc., there might be fun; who knew? Carlyle, too, makes loud Scottish-Covenanter gruntings of laudation, or at least of consideration, when anything strikes him, to the edifying of the attentive vicinity. As it befell, no harm was done; no knives were concealed in the words, more 's the pity! Many things — supposed by some to be important, but on which the better part suspended their judgment — were propounded, and the assembly at last escaped without a revolution. Lord Morpeth sent me a compliment in a note, and I am to dine with him on the 28th. The Duchess of Sutherland sent for me to come to lunch on Monday, and she would show me her house. Lord Lovelace called on me on Saturday, and I am to dine with him to-morrow, and see Byon's daughter. I met Lady Byron at Mrs. Jameson's, last week, one evening. She is a quiet, sensible woman, with this merit among others, that she never mentions Lord Byron or her connection with him, and lets the world discuss her supposed griefs or joys in silence. Last night I visited Leigh Hunt, who is a very agreeable talker, and lays himself out to please; gentle, and full of anecdote. And there is no end of the Londoners. Did I tell you that Carlyle talks seriously about writing a newspaper, or at least short off-hand tracts, to follow each other rapidly, on the political questions of the day? I had a long talk with him on Sunday evening, to much more purpose than we commonly attain. He is solitary and impatient of people; lie has no weakness of respect, poor man, such as is granted to other scholars I wot of, and I see no help for him. ... I have been taxed with neglecting the middle class by these West-End lectures, and now am to read expiatory ones in Exeter Hall; only three, — three dull old songs.

one's sister: Elizabeth Hoar had been engaged to marry Emerson's brother Charles. Although Charles died of tuberculosis before the wedding could take place, Emerson subsequently considered Hoar to be as a sister and addressed her accordingly.

Reading room of the British Museum in Punch; source: ncgsjournal.com

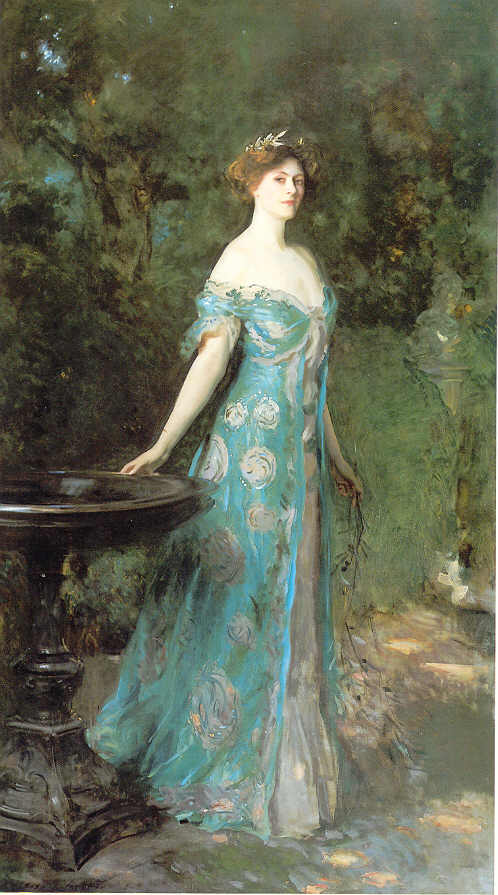

Portrait of Anne Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, Duchess of Sutherland by John Singer Sargent; source: jssgallery.org

the Marylebone course: This refers to Emerson's final series of London lectures.

Massachusetts Indian: Ironic reference to himself as outlander in English eyes.

Carlyle and Monckton Milnes, etc.: Emerson's friends, previously descrbied in this series of blog posts.

Earl of Lovelace was husband of Byron's daughter Ada.

Note on finding other posts in this series: All have the tags Emerson, journal, and 1848.

Some sources:

A memoir of Ralph Waldo Emerson, by James Elliot Cabot (Cambridge, Printed at the Riverside Press, 1887)

A Memoir of Ralph Waldo Emerson, by James Elliot Cabot (Houghton Mifflin and company, 1887)

Ralph Waldo Emerson on Transcendentalism Web (vcu.edu)

No comments:

Post a Comment