By the middle of the nineteenth century anti-Catholic and anti-Irish hostility was common in New York and the New England states. Americans aped the British in their fear of Popery and condemned the Irish as a sub-human species. Below the text I've reproduced some bigoted cartoons that reflect these prejudices.

Catholics in general and the Irish in particular resisted these attacks and eventually overcame them. They did this partly by assimilation — demonstrating to the Protestant ascendancy that there was nothing to fear — and partly through self-assertion — demonstrating the power of their solidarity, discipline, and force of numbers.

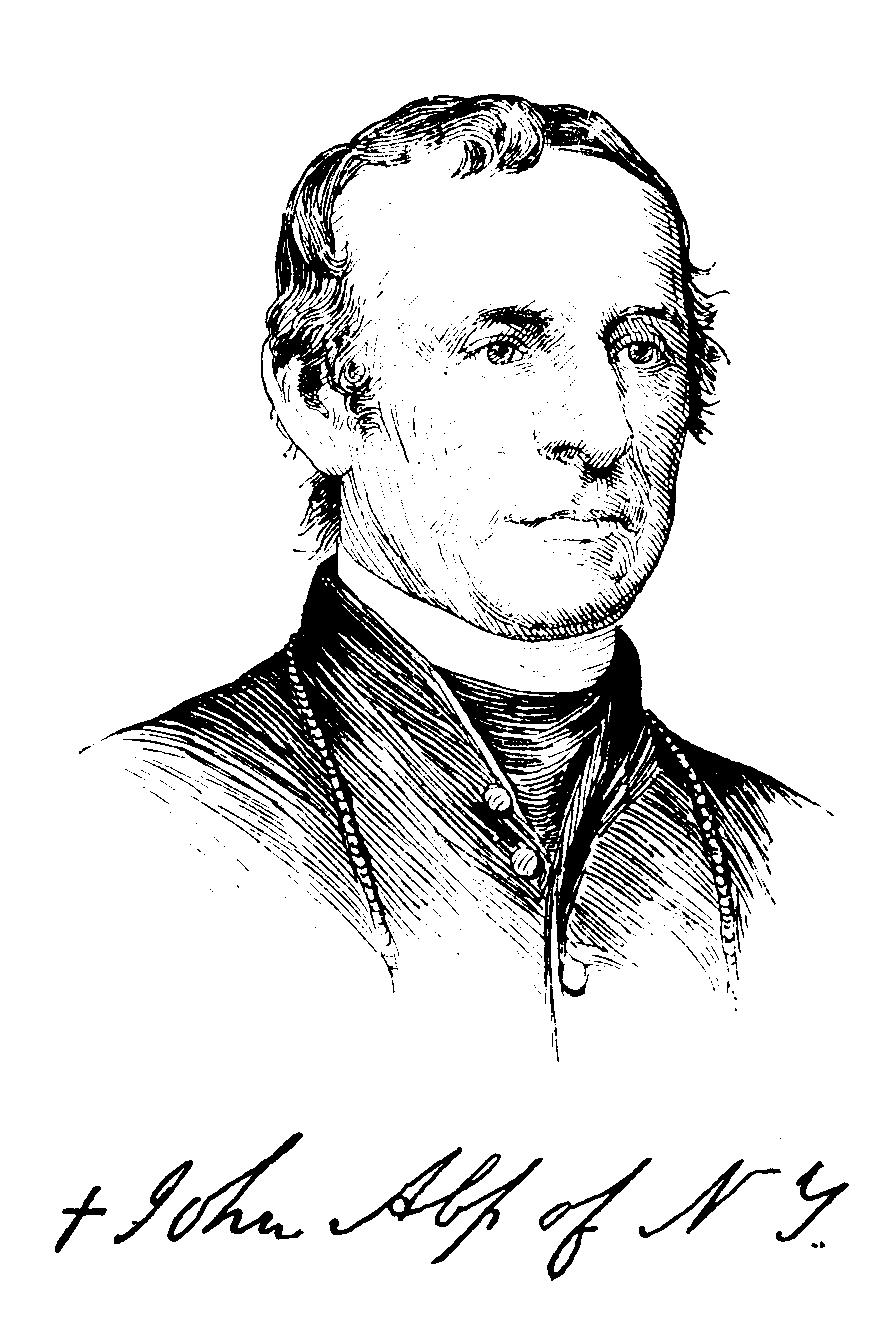

And they did it with the impassioned leadership of an Irish-American priest,

John Hughes. This was much more than a spiritual leadership. Hughes gained authority within the Church by his determination, polemical skills, and a large measure of bullying. Stubbornly, he overcame resistance to men who wished to deny him a Catholic education, and those, later, who wished to deny him the priesthood, advancement into the ranks of New York's bishops, and selection as the city's archbishop. As he forcefully attacked those who would resist his advance, so also he attacked those he considered to enemies of the Church and of the hundreds of thousands of Catholic immigrants who arrived from Ireland during his lifetime.

His feisty demeanor, along with a habit of putting a cross by his signature, earned him the nickname "Dagger John" in the local press, but he was not so fierce in private. If

Dagger John was utterly fearless, possessing an indomitable will, unwavering resolution, firmness of purpose, he was also warm and generous. Equally able to express both genial humor and cutting sarcasm, he had a sensitive nature and a gift for establishing and nurturing close friendships.[1]

To my mind this detail from a portrait shows empathy and the nurturing side of his character.

{Matthew Brady made this portrait of Hughes after he became archbishop; source: wikipedia}

Further down this page I've given a short biography of the man and his works; the Sources section (also below) gives links for lots more information about him. His achievements are extensive. One of his biographers says "It is an understatement to say that John Hughes was a complex character. He was impetuous and authoritarian, a poor administrator and worse financial manager, indifferent to the non-Irish members of his flock, and prone to invent reality when it suited the purposes of his rhetoric."[2] But as another says, "Dagger John Hughes proved himself a formidable force in an era when a fighting bishop was needed. When the Vatican nuncio, Archbishop Bedini, asked an American priest to explain why people in America held Archbishop Hughes in such esteem, the answer was: 'It is because he is always game.'"[3] And a third calls him "a master-builder of the Church in the United States and one of the most helpful and sagacious of the makers of America" and "a prelate and citizen whose strong personality, indomitable courage, and invaluable service constituted him the man needed in his day to meet critical conditions."[4]

Hughes had no illusion about the state of Irish immigrants in New York, calling them "the poorest and most wretched population that can be found in the world — the scattered debris of the Irish nation."[5] He said this to describe not condemn. His feelings for Irish-Americans and the Irish homeland were as strong as was his commitment to his vocation and the Church.

You can see this deep compassion in a speech he gave at the height of the Irish famine. It is an oration in the classical mode -- majestic, Ciceronian, persuasive, articulate, and impassioned. In it he condemns the British state for its evil policies, gives no quarter, and takes no prisoners. He does not praise the starving Irish for the patient endurance and Christian forbearance they have shown under unmerited English durance, but says they have the right to seize for themselves the food that their landlords were sending out of Ireland in the midst of the potato famine.

He condemns the English governing class for imprisoning itself in "a defective or vicious system of social and political economy" and he tells his listeners that this system has become the "great cause of Ireland's peculiarly depressed condition."

He says, "The fault that I find with [this system of social and political economy] is, that it provides wholesome food, comfortable raiment and lodgings for the rogues, and thieves, and murderers of the dominions, whilst it leaves the honest, industrious, virtuous peasant to stagger at his labour through inanition, and fall to rise no more."

He tells us of an "admirable resignation," praised by Ireland's overlords: "This same political economy authorises the provision merchant, even amidst the desolation, to keep his doors locked, and his sacks of corn tied up within, waiting for a better price, whilst he himself is, perhaps, at his desk, describing the wretchedness of the people and the extent of the misery; setting forth for the eye of the first lord of the treasury with what exemplary patience the peasantry bear their sufferings, with what admirable resignation they fall down through weakness at the threshold of his warehouse, without having even attempted to burst a door, or break a window."

But he does not himself praise this patient fortitude: "The rights of life are dearer and higher than those of property; and in a general famine like the present, there is no law of Heaven, nor of nature that forbids a starving man to seize on bread wherever he can find it, even though it should be the loaves of proposition on the altar of God's temple."[6]

And he concludes by describing the impersonal obliteration of a people: "The vice which is inherent in our system of social and political economy is so subtile that it eludes all pursuit, that you cannot find or trace it to any responsible source. The man, indeed, over whose dead body the coroner holds the inquest, has been murdered, but no one has killed him. There is no external wound, there is no symptom of internal disease. Society guarded him against all outward violence; it merely encircled him around in order to keep up what is termed the regular current of trade, and then political economy, with an invisible hand, applied the air-pump to the narrow limits within which he was confined, and exhausted the atmosphere of his physical life. Who did it? No one did it, and yet it has been done."

At end, he calls upon the spirit within the Irish which will survive and again flourish: "There was this one sovereignty which they never relinquished — the sovereignty of conscience and the privilege of self-respect. Their soul has never been conquered; and if it was said in Pagan times that the noblest spectacle which this earth could present to the eye of the immortal gods, was that of a virtuous man bravely struggling with adversity, what might not be said of a nation of such men who have so struggled through entire centuries? Neither can it be said that their spirit is yet broken. Intellect, sentiment, fancy, wit, eloquence, music, and poetry, are, I might say, natural and hereditary attributes of the Irish mind and the Irish heart; and if no adversity of ages was sufficient to crush these capacities and powers, who will say that such a people have not, under happier circumstances, within themselves a principle of self-regeneration and improvement, which will secure to them at least an ordinary portion of the happiness of which they have been so long deprived?"[7]

--------------------

This is the how John Hughes signed himself. The cross by his name gave the excuse for his nickname.

Here is the full portrait by Matthew Brady.

Here are some anti-Catholic and anti-Irish cartoons from nineteenth century America. Many were by Thomas Nast and appeared in

Harper's Weekly, a paper with Republican, and thus anti-Democratic, anti-Irish, and anti-Catholic sympathies.

1. Showing Irish-Americans as anti-assimilationist. For many of them, as for Hughes, Irish solidarity was a source of strength, in resistance to American prejudices, in development of a political and economic power base, and in insuring close ties with the old homeland.

{The Mortar of Assimilation and the One Element that Won't Mix, Puck, June 26, 1889; source: museum.msu.edu}

2. The LC caption to the cartoon reads: The Usual Irish Way of Doing Things, a savage anti-Irish cartoon by Thomas Nast, depicting a drunk Irishman lighting a powder keg and swinging a bottle. Published 1871-09-02 in Harper's Weekly.

{Political cartoon titled "The Usual Irish Way of Doing Things" by Thomas Nast (1840-1902) published in Harper's Weekly on 1871-09-02; source: wikipedia }

3. This savage caricature shows Irish-Americans as sub-human beings as its caption states.

{source: salon.com/blog/marygrav (reviewing: Race: A History Beyond Black and White by Marc Aronson (2007)}

4. This is a complex cartoon by Nast on the city's cancellation of a parade by Protestant Irish-Americans because of expected disruption by Catholic ones.[8]

{Harper's Weekly, July 29, 1871: Thomas Nast, “Something That Will Not ‘Blow Over'” source: assumption.edu}

5. New York's Irish-American vote grew increasingly potent as the nineteenth century proceeded. At first most Irish-Americans voted against the Tammany Hall political machine, but they later exploited it to their great advantage. Tammany's party were the Democrats. This cartoon shows an Irish-American thug and a Catholic priest carving up the Democratic Party, shown as the goose that laid the golden eggs.

{By Thomas Nast; source: latinamericanstudies.org}

6. This vicious Thomas Nast cartoon speaks for itself.

{Nast depicted the Irish as violent ape-like creatures; source: latinamericanstudies.org}

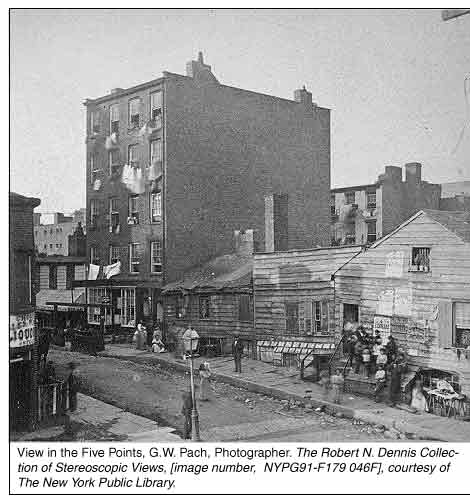

7. It's 1868 and a Southern rebel, the Democratic Party presidential candidate, and an Irish thug are joining forces to defeat the Republican Party's Reconstruction policies and stomp on newly freed slaves. Notice that the Irishman has "5 Points" written on his hat.

{Harper's Weekly, Sept. 5, 1868}

----------------

Brief biography of John Hughes:

The embodiment of this trend toward an authoritarian clergy and hostility to evangelical Protestant reform was John Hughes (1797-1864), bishop of New York. Born in County Tyrone he came to the U.S. in 1818 and soon entered Mount St. Mary’s seminary in Maryland. Ordained in 1826 he soon achieved a national reputation as a fiery pro-Catholic polemicist, engaging in several high profile “debates” in the pages of leading Protestant and Catholic newspapers. His detractors took to calling him “Dagger John” because of his personality and the fact that he always drew a dagger-like cross under his signature.

He was made Bishop of New York in 1842 (and Archbishop in 1850). He became a leading figure in the reshaping of the American Catholic Church along Irish lines – that is a militant brand of worship that emphasized obedience, piety, regular worship, and reception of the sacraments -- backed by an authoritarian clergy. Central to this plan was a program of institution building designed to insulate Catholics from the corrupting influences of American culture. This included not just parish building, but the establishment of a vast system of parochial schools, hospitals, and orphanages, plus separate fraternal societies to compete with American ones. On more than one occasion, Hughes mused that it might be more important to build a parochial school first, followed by the parish church. This outlook was understandable, given the hostile environment of his era. However, critics then and in subsequent generations have argued that in the long run Hughes’ model of defensive Catholicism hindered the full participation of Catholics in American life until the mid-20th century.

-- "Dagger John" Hughes by Edward T. O'Donnell

------------

Some sources:

DEATH OF ARCHBISHOP HUGHES.; HIS SICKNESS AND LAST MOMENTS. SKETCH OF HIS LIFE, New York Times, January 4, 1864

Complete works of the most Rev. John Hughes, archbishop of New York: comprising his sermons, letters, lectures, speeches, etc edited by Lawrence Kehoe (Lawrence Kehoe, 1866)

Complete works of the most Rev. John Hughes, archbishop of New York: comprising his sermons, letters, lectures, speeches, etc, Volume 2 edited by Lawrence Kehoe (Lawrence Kehoe, 1866)

Life of the Most Reverend John Hughes, D.D.: first archbishop of New York. With extracts from his private correspondence Volume 257 of American culture series by John Rose Greene Hassard (D. Appleton and company, 1866)

Biographical sketch of the Most Rev. John Hughes, D. D. archbishop of New York by the Office of the "Metropolitan record", 1864

Archbishop John Hughes by William J. Stern

Archbishop John Hughes and Irish Catholicism in New York by Richard McCarthy

New York's Catholic Century, New York Times, by Peter Quinn, June 4, 2006

Archbishop John J. Hughes (1797-1863) by the Lincoln Institute

John Hughes (archbishop)Refractive History: Memory and the Founders of the Emigrant Savings Bank

Author(s): Marion R. Casey

Source: Radharc, Vol. 3 (2002), pp. 55-96

Published by: Glucksman Ireland House, New York University

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25114415

Immigrants in the City: New York's Irish and German Catholics

Author(s): Jay P. Dolan

Source: Church History, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Sep., 1972), pp. 354-368

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the American Society of Church

History

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3164221

The New York Irish ed. by Ronald H. Bayor and Timothy J. Meagher (JHU Press, 1997)

Irish American SolidarityThe Irish (in countries other than Ireland) In the United StatesFrom Famine to Five Points: Lord Lansdowne's Irish Tenants Encounter North America's Most Notorious Slum by Tyler Anbinder,

American Historical Review, Vol. 107, No. 2, April 2002.

The Catholic encyclopedia: an international work of reference on the constitution, doctrine, discipline, and history of the Catholic ChurchHow Dagger John Saved New York's Irish by William J. Stern

Archbishop John Hughes and the Church in New York by Thomas J. Shelley

CITY LORE; New York's Catholic Century by Peter Quinn, New York Times, June 4, 2006

Harper's Weekly, July 29, 1871: Thomas Nast, “Something That Will Not ‘Blow Over'”Anti-Irish racismNativism and Bigotry Thomas Nast-------

Notes:

[1] Paraphrased from

Biographical sketch of the Most Rev. John Hughes, D. D. archbishop of New YorkOffice of the "Metropolitan record", 1864. Here's the extract:

The brave heart of the Bishop throbbed as evenly when his home and life were threatened by a bigoted and insensate mob, as it did when presiding over a Diocesan Convention in his own episcopal city. Indeed, his utter fearlessness, his unwavering resolution, his indomitable will, and his firmness of purpose, gained him the esteem of generous opponents, and awakened in meaner minds a salutary dread of coming in conflict with him. Not in the United States alone was his preeminence acknowledged and his lofty qualities appreciated — in every part of the Catholic world his name was a household word. Ireland placed him high among her noblest and most gifted sons, and Rome regarded him as one of the staunchest pillars of the Church of God.

The love and pride that Ireland felt in him he repaid in kind. Throughout all his life he took a deep and abiding interest in everything that concerned her, everything that affected her for weal or woe. Next to his devotion to the Church, and his love for the people committed to his spiritual care, was his love for Ireland, the land from which he derived his most striking characteristics — his genius, his intellectual combativeness, his force of will, his quick perception, his pride of race, his cutting sarcasm and his genial humor, his generosity, his warm feelings, and his sensitiveness on the point of fame or reputation. His generosity was as unostentatious as it was untiring. The writer of this was cognizant of many and many an act of munificent generosity so delicately bestowed that to the recipients it seemed rather a friendly gift than a charitable donation.

[2] Found in

Archbishop John J. Hughes (1797-1863) by the Lincoln Institute

[3] Quoted in

Pope at St. Patrick’s in New York: We Owe Bishop Hughes[4] By J. B. wainewright in

The Catholic encyclopedia. Here's the whole paragraph:

He lived and passed away amid stirring times; it was providential for Church and country that he lived when he did. His natural gifts of mind and heart, independent of his education, were of a high order and made him pre-eminent in leadership; not only was he a great ruler of an important diocese in a hierarchy remarkable for distinguished bishops, but also a master-builder of the Church in the United States and one of the most helpful and sagacious of the makers of America. Church and nation are indebted forever to the prelate and citizen whose strong personality, indomitable courage, and invaluable service constituted him the man needed in his day to meet critical conditions. He was resolute, fearless, far-sighted, and full of practical wisdom based on the sanest and soundest principles. To bring out the innate power within him required but the opportunity presented by the Church struggling for a footing in a rather hostile community, anoby the nation endeavouring to cope with harassing questions at home and impending trouble abroad. His failures were few; his achievements many and lasting. He was feared and loved; misunderstood and idolized; misrepresented even to his ecclesiastical superiors in Rome, whose confidence in him, however, remained unshaken. Severe of manner, kindly of heart, he was not aggressive until assailed.

[5] Archives of the University of Notre Dame, (hereafter referred to as AUND), Bishop John Hughes to Society for the Propagation of the Faith, Paris, June 26, 1849, f. 104; Browne, "The Archdiocese of New York a Century Ago," p. 165. This is quoted in: "Immigrants in the City: New York's Irish and German Catholics" by Jay P. Dolan,

Church History, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Sep., 1972), pp. 354-368, retrieved from jstor: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3164221

[6] The

Loaves of Proposition were the "Hallowed Bread" of the Hebrews' tabernacle. They were specially prepared, unleavened, and are also know in English as show-bread and presence-bread.

[7] Here's more of the context of this part of the speech.

I have not come here to enlarge upon the feelings of sympathy that have been aroused in our own bosoms, nor yet on those of gratitude that will soon be awakened in the breasts of the Irish people. I come, not to describe the inconceivable horrors of a calamity which, in the midst of the Nineteenth Century, eighteen hundred and forty seven years after the coming of Christ, either by want or pestilence, or both combined, threatens almost the annihilation of a whole Christian people. The newspapers tell us that this calamity has been produced by the failure of the potato crop; but this ought not to be a sufficient cause of so frightful a consequence; the potato is but one species of the endless varieties of food which the Almighty has provided for the sustenance of his creatures; and why is it that the life or death of the great body of any nation should be so little regarded as to be left dependent on the capricious growth of a single root? Many essays will be published; many eloquent speeches pronounced; much precious time unprofitably employed, by the State economists of Great Britain, assigning the cause or causes of the scourge which now threatens to depopulate Ireland. I shall not enter into the immediately antecedent circumstances or influences that have produced this result. Some will say that it is the cruelty of unfeeling and rapacious landlords; others will have it, that it is the improvident and indolent character of the people themselves; others, still, will say that it is owing to the poverty of the country, the want of capital, the general ignorance of the people, and especially their ignorance in reference to the improved science of agriculture. I shall not question the truth or the fallacy of any of these theories; admitting them all, if you will, to contain each more or less of truth, they yet do not explain the famine which they are cited to account for. They are themselves to be accounted for, rather as the effect of other causes, than as the real causes of effects, such as we now witness and deplore. ...

I have ventured to suggest a defective or vicious system of social and political economy as the other great cause of Ireland's peculiarly depressed condition. By social economy I mean that effort of society, organized into a sovereign State, to accomplish the welfare of all its members. ... The fault that I find with the system is, that it not only allows but sanctions and approves of a principle, which operates differently in two provinces of the same State, divided only by a channel of the sea. It multiplies deposits of idle money in the banks, on one side of that channel, and multiplies dead and coffinless bodies in the cabins, and along the highways, on the other. The fault that I find with it is, that it guarantees the right of the rich man to enter on the fields cultivated by the poor man whom he calls his tenant, and carry away the harvest of his labour, and this, whilst it imposes on him no duty to leave behind at least food enough to keep that poor man alive, until the earth shall again yield its fruits. The fault that I find with it is, that it provides wholesome food, comfortable raiment and lodgings for the rogues, and thieves, and murderers of the dominions, whilst it leaves the honest, industrious, virtuous peasant to stagger at his labour through inanition, and fall to rise no more. ...

They call its God's famine! No! no! God's famine is known by the general scarcity &mdash there has been no general scarcity of food in Ireland either the present or the past year except in one species of vegetable. The soil has produced its usual tribute for the support of those by whom it has been cultivated; but political economy found the Irish people too poor to pay for the harvest of their own labor, and has exported it to a better market, leaving them to die of famine, or to live on alms; and this same political economy authorises the provision merchant, even amidst the desolation, to keep his doors locked, and his sacks of corn tied up within, waiting for a better price, whilst he himself is, perhaps, at his desk, describing the wretchedness of the people and the extent of the misery; setting forth for the eye of the first lord of the treasury with what exemplary patience the peasantry bear their sufferings, with what admirable resignation they fall down through weakness at the threshold of his warehouse, without having even attempted to burst a door, or break a window.

The rights of life are dearer and higher than those of property; and in a general famine like the present, there is no law of Heaven, nor of nature that forbids a starving man to seize on bread wherever he can find it, even though it should be the loaves of proposition on the altar of God's temple.

The vice which is inherent in our system of social and political economy is so subtile that it eludes all pursuit, that you cannot find or trace it to any responsible source. The man, indeed, over whose dead body the coroner holds the inquest, has been murdered, but no one has killed him. There is no external wound, there is no symptom of internal disease. Society guarded him against all outward violence; it merely encircled him around in order to keep up what is termed the regular current of trade, and then political economy, with an invisible hand, applied the air-pump to the narrow limits within which he was confined, and exhausted the atmosphere of his physical life. Who did it? No one did it, and yet it has been done.

There was this one sovereignty which they never relinquished — the sovereignty of conscience and the privilege of self-respect. Their soul has never been conquered; and if it was said in Pagan times that the noblest spectacle which this earth could present to the eye of the immortal gods, was that of a virtuous man bravely struggling with adversity, what might not be said of a nation of such men who have so struggled through entire centuries?

Neither can it be said that their spirit is yet broken. Intellect, sentiment, fancy, wit, eloquence, music, and poetry, are, I might say, natural and hereditary attributes of the Irish mind and the Irish heart; and if no adversity of ages was sufficient to crush these capacities and powers, who will say that such a people have not, under happier circumstances, within themselves a principle of self-regeneration and improvement, which will secure to them at least an ordinary portion of the happiness of which they have been so long deprived? The charity of other countries, and among them pre-eminently of England herself, the sympathy of distant and free States, on this occasion, will themselves have an effect. They will show Ireland that she is cared for; they will inspire her with the pleasing hope that she is not to be always the down-trodden and neglected province, the outcast nation among the nations of the earth.

-- A Lecture on the Antecedent Causes of the Irish Famine in 1847. Delivered Under the Auspices of the General Committee for the Relief of the Suffering Poor of Ireland, by The Right Rev. John Hughes, D. D., Bishop of New York, at the Broadway Tabernacle, March 20, 1847, in Life of Archbishop Hughes, with a full account of his funeral, Bishop McCloskey's oration, and Bishop Loughlin's month's mind sermon. Also Archbishop Hughes' Sermon on Catholic emancipation and his great speeches on the school question : including his three days' speech in Carroll Hall ..., Volume 1 (American News Co., 1864)

[8] Here's a full explanation of the cartoon.

Unlike present-day editorial cartoons, which typically feature a single, immediately recognizable image, Thomas Nast and his contemporaries assumed that readers would spend the time needed to completely "read" their works. In "Something That Will Not 'Blow Over'" students encounter one of Nast's most complex and most compelling cartoons, one that says much about the racial and ethnic tensions of the period surrounding the Civil War and how they were complicated by New York City politics.

Nast's double-page cartoon on the July 12th Orange Riot appeared only a few days after the New York Times began its exposé of the Tweed Ring. The Times editorialized on July 20 that: "Everybody should see, and seeing, retain Nast’s great 'Riot Cartoons' in the New Number of Harper's Weekly."

The Orange parade commemorated the victory of the Protestant William of Orange, the new king of England, over the Catholics in the Battle of the Boyne in Ireland in 1692 and was celebrated annually by Protestants in Ireland and, starting in 1870, in New York. Both Nast and Harper's Weekly thought that the Irish Catholics were a bane and that the Protestant Irish deserved the full protection of the city, state, and nation in their expression of their loathing of the Irish Catholics. The Catholic Irish had rioted during the 1870 parade. In 1871 they petitioned New York City officials to ban the Orange parade.

On July 10, Police Superintendent James J. Kelso denied the Orangemen a permit on the grounds that the parade would threaten public safety, an ironic tribute to the previous year's riot, and that obscene or violently derogatory language or gestures in public were misdemeanors. In 1870 both groups had engaged in such behavior before getting down to physical measures. Irish Catholics praised the decision, which was endorsed by William "Boss" Tweed of Tammany Hall, the Democratic political machine that controlled city government. Irish Protestants of course objected. They pointed out that not only did Catholic Irish routinely receive a permit for the annual St. Patrick's Day parade but also that the mayor and others routinely attended it. They claimed a right to equal treatment. Governor John Hoffman intervened, the permit was granted, and the parade and the riot got underway just after noon on July 12.

Nast's title drew upon the initial response of "Boss" Tweed to the Times stories of municipal corruption, that they were much ado about nothing and would soon "blow over." The central image, under the heading "Has no caste, no sect, no nation, any rights that the infallible, ultramontane Catholic is bound to respect," portrays gorilla-like Irish thugs assaulting a parade that includes not just Orangemen but virtually every other group in America. They include Chinese, Native Americans, blacks, Free Masons, liberal Catholics, and Germans. The burning orphanage and the lynching recall two of the most notorious excesses of the 1863 Draft Riot. The heading paraphrases the Dred Scott Decision in which Chief Justice Taney ruled that blacks had no rights that whites were bound to respect. Many New York Democrats, including the Irish, had supported the decision. The "infallible, ultramontane" modifiers of Catholic refer to the recent proclamation of papal infallibility in matters of faith and morals at the 1870 Vatican Council and to the allegiance all Catholics owed to the Pope in Rome (over the mountains from a German perspective; Nast was a German Protest immigrant). Note that the American flag is flying upside down while the new standard of "Centralization" with Tammany and Popery flanking an Irish harp proudly waves from a flagpole topped with a cross.

The upper left panel shows Columbia rewarding the police and National Guard troops who protected the Orangemen. Just below the "people" rise up, led by Columbia before whom cower members of the Tweed Ring. Below that Columbia speaks. In the opposite corner is "Pat's Complaint." In between is another caricature of the Tweed Ring, this time portrayed as "slaves" of the Irish. The header — "Well, what are you going to do about it?" — turns another Tweed response to the corruption allegations into a taunt aimed at the Ring. The "slaves" description complements the panel just above "Pat's Complaint" in which Tweed and his cohorts give in to the Catholic demand that the city ban the Orange parade. The upper right panel indicates the significance of July 12 to the Orangemen and highlights their offer to discontinue their parade if the Catholic Irish would cease marching on St. Patrick's Day. A haughty Irish "pope" replies: NIVIR!

-- July 12th Orange Riot