Five Points came into existence after a canal was cut along a meandering creek to drain a body of water called Collect Pond. This drawing somewhat fancifully shows the appealing nature of this little lake in 1798. The artist was standing about where Mulberry Street would later be laid down.[2]

This lithograph shows the pond as it looked in 1796. I think the artist is standing on the east side looking west.

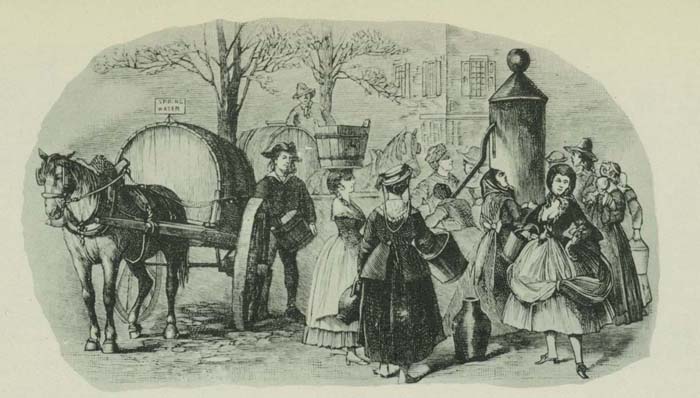

This print from the early nineteenth century shows locals at one of the pumps that tapped the spring which fed Collect Pond.

As the source of the print explains, this pump dispensed tea-water not in the sense that it was brown and brackish, but rather that it was clear, sweet-tasting, and suitable for use in brewing expensive Indian tea.

This shows a more famous tea-water pump, located to the southeast of the pond.

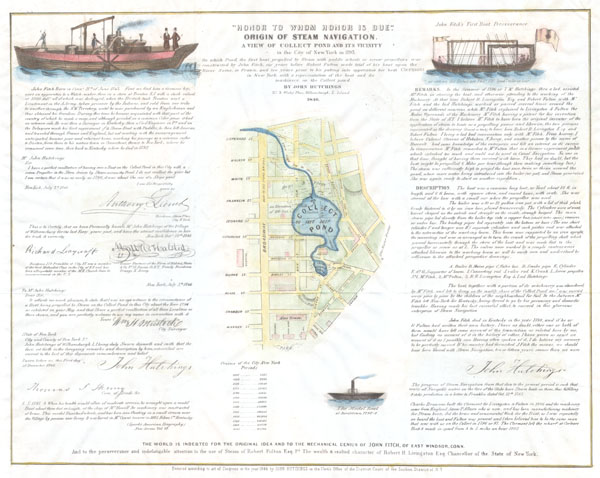

This map of lower Manhattan in 1803 shows the location of the Collect Pond, Mulberry St., Tea-Water Pump, and Pump St. Knapp's Pump is off map to the north and west. Pump Street was named to commemorate Teawater Pump and adjacent Teawater Gardens.[3]

You'd think Collect Pond got its name from its job of collecting water from the spring that fed both it and the nearby pumps. Not so; collect is a corruption of the Dutch word kolk meaning a small body of water. Kolk morphed into kolch and then kalch before getting Englished to collect. This map gives the old name.

You can see from this map that the spring-fed pond emptied by rivulets both east and west across the island. In fact, one source says before the arrival of Europeans the indigenous Native Americans could — during the spring floods — paddle from the East River to the Hudson River through the Collect Pond.[4]

The steamboat in the print by Philip Meeder that I reproduced above shows the first successful experiment in the US to build a working steamboat. In the summer of 1796, the designer, John Fitch, selected Collect Pond as the place to show off his achievement. As the world knows, it was Robert Fulton who eventually produced the first commercially successful steamboat, launching it in the nearby Hudson.[5]

By the time Fitch conducted his test the pond was making a transition from the bucolic spot shown in Robertson's and Meeder's pictures and was being inundated with noxiousness: slaughterhouses, tanneries, gunpowder storage facilities, seasonally-flooded bogs, and prisons. As early as 1798, the year of Robertson's watercolor, it was described as "a shocking hole, where all impure things centre together and engender the worst of unwholesome productions."[6]

A few years later, in an action of urban cleansing, the pond was drained and filled in to make room for more buildings in which to house the city's growing population. A canal was dug along the stream that fed from the pond to the Hudson on its west and a new road, Canal Street, was constructed by its banks.

This 1811 lithograph shows the drainage canal as it passes under a bridge at Broadway. Canal Street runs on both sides of the water.

After the canal drained off most of the water, "Bunker Hill," the little hill in Robertson's watercolor, was leveled and its mass used to fill the wetlands that remained. By 1813 there were no visible remains of pond or hill.[7]

A nineteenth-century historian explains the city's next actions:

At the spring election of 1835 a most serious question was submitted to the decision of the people. New-York had never enjoyed any proper and reasonably assured water-supply for a population of her extent and promise. The tea-water works, which were put up in 1786 at the Collect pond, or Fresh Water, had supplied the city by casks until 1799, when the Manhattan Company was chartered to bring a supply from the Bronx River. A pump was built near the Collect and wooden pipes laid through the streets, but the Manhattan Company never tapped the waters of the Bronx, and the city was forced to content itself with the old Collect supply. ... It was now decided by popular vote, by a large majority, to construct an aqueduct from the Croton River, an undertaking of great magnitude in those days, considering that the distance the water had to be conveyed was forty miles.I've written previously about Croton Aqueduct and some of its many associations.[8]

-- The Memorial History of the City of New-York: From Its First Settlement to the Year 1892, Vol. 3, ed. by James Grant Wilson (New York History Co., 1893)

The aqueduct, which was the greatest engineering feat yet attempted in the US, proved to be a great success. New Yorkers celebrated extravagantly when its waters first flowed in for their use. To show how great was the achievement and how abundant the water, the city set up fountains, including this one, just south of the place where Collect Pond and the Chatham Street Tea-Water Pump had been located.

Despite drainage and in-filling, the area around Collect Pond remained marshy, mosquito-ridden, and unwholesome. Being unhealthy, the land was cheap. Being infirm, it could not support multi-storied brick buildings, but only small brick or wooden frame structures. The resulting cheapness of land and its dwellings meant that the area became a magnet for the city's poorest citizens, those who could afford no other place to live. Out of this mix, the slum called Five Points was born.

This lithograph depicts the center of the slum, in Five Points intersection itself, just 14 years after the pond was covered over.

As you can see from this detail, there was then a pump drawing water from the spring that still flowed under feet of the area's residents.

Some additional sources:

Collect Pond on wikipedia

Collect Pond, Manhattan from the New York Public Library

The Documentary history of the state of New-York The Documentary history of the state of New-York: arranged under direction of the Hon. Christopher Morgan, secretary of State, Volume 2, ed. by Edmund Bailey O'Callaghan (Weed, Parsons & co., public printers, 1849)

Collect Pond on the New York Parks web site

Canal Street on forgottenny.com

THE FIVE POINTS on urbanography.com

Evolution of City Hall Park and Foley Square from nymapsociety.org

1850 US Census of the New York City Prison AKA The Tombs on rootsweb.ancestry.com

Harper's magazine, Vol. 98, 1899, "A Historic Institution. The Manhattan Company — 1799-18989" by John Kendrick Bangs (Harper's Magazine Co., 1899)

Collect Pond in New York City Map and Steamship Test Print, 1846 on georgeglazer.com

The Life of John Fitch the Inventor of the Steamboat by Thompson Westcott (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1857)

-------------

Notes:

[1] Here are the blog posts on Mulberry Street so far:

Mulberry Street 1900[2] A curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art writes of this picture: "The natural pool Collect Pond was located in lower Manhattan near present-day Foley Square. This watercolor of the site exemplifies the formulaic method of drawing taught at the Columbian Academy of Painting in New York City, founded by the brothers Archibald and Alexander Robertson. Both the hill at left and the willow tree at right were rendered in highly stylized fashion, with broad contours and schematic curving lines. Spatial depth was achieved with swaths of dark wash in the foreground, setting off the lighter forms in the distance. Indeed, the whole picture observes a kind of artistic etiquette embodied in the polite company of figures in the foreground."

Mulberry Street, again

a tenement on Mulberry Street

five-cent den on Pearl St.

[3] This map shows the pond in 1793 overlayed by 19th-c. streets.

[4] In a web page called Evolution of City Hall Park and Foley Square, Philip Ernest Schoenberg, writes:

For hundreds of years, the area had been the site of an Indian village. ... The Indians were part of the Leni Lenape, Algonquin, or Delaware people. The population on the site may have been between 5,000 and 10,000. The total Leni Lenape population of Manhattan Island may have been as high as 30,000 and the New York metropolitan area may have been 65,000. Diseases reduced the native population of the area to 200 by the year 1700.[4] Wikipedia's article on John Fitch says he "was an American inventor, clockmaker, and silversmith who, in 1787, built the first recorded steam-powered boat in the United States." Two decades later, Robert Fulton was able to make steamboats profitable. This broadside celebrates Fitch's achievement.

The village was known as “Werpoes” or “Hare” in the language of the Algonquin Indians. They were semi-nomadic. The village would move each planting season as the Indians burned the woods to gain new land to farm and let old land recover. The Leni Lenape planted the “Three Sisters” — squash, corn, and beans. They would also go to Washington Heights and Inwood neighborhoods of Manhattan to hunt deer and other animals. ...

In the Dutch period, the area was set aside as a Commons where anyone could graze a cow or sheep for free. It also became the ceremonial area for parades, celebrations, executions, and public gatherings. ...

In the British period, the area that had been center of the Indian village became the African Burial Ground. The blacks, slave and free, segregated in life, were segregated in death and were not permitted to be buried in the churchyards. By the end of the eighteenth century, the area was forgotten as residential development moved northward. An estimated 15,000 to 20,000 Africans and African-Americans were buried between today's Chambers and Reade Streets, Broadway and Centre Streets.

Description: An extremely scarce 1846 broadside issued by John Hutchings to promote the awareness of John Fitch as a pioneer of steam navigation. Fitch was an instrument maker working in the later part of the 18th century. As an early pioneer of steam navigation, Fitch tested several steamboats on the Delaware River between 1785 and 1788. One of these, the Perseverance, is depicted in the upper right quadrant of this sheet. Fitch’s real success, however, occurred a few years later when, in 1793 he tested another ship equipped with a paddle wheel on New York’s Collect Pond. This was a full six years before Fulton and Livingston launched “Fulton’s Folly” on the Seine. Hutchings claims to have been a “lad” at the time who “assisted Mr. Fitch in steering the boat”. Hutchings asserts that it was in fact Fitch who designed the steam propulsion mechanism. He claims that both Fulton and Livingston were present during the Collect Pond tests and in fact depicts both, as well as Fitch and himself, in a paddlewheel steam ship in the upper left quadrant. Though Fulton seems to have received most of the credit for the era of steam navigation, Hutchings hoped, through the publication of this broadside, to shed some light on Fitch’s contributions as well. Central to this publication is a map of the Collect Pond and vicinity extending roughly from Broadway westward to Chatam Street, south as far as City Hall Park and north to Canal. Roughly between Barlet Street and Franklin rested the Collect Pond, a natural depression and drainage area that filled with water seasonally. The Collect Pond appears in early maps of New York City and until the construction of the Croton Aqueduct was one of the few sources of fresh water in lower Manhattan. This pond was filled in around 1811 when it transformed into the notorious and poverty stricken "Five Points" district. When Fitch tested his steamboat the pond would have been surrounded by slaughterhouses, tanneries, gunpowder storage, bogs and prisons – not exactly a pretty place for an afternoon boat ride. The map image is surrounded by a brief biography of Fitch, signed attestations from important figures regarding the character of Fitch and Hutchings, and eye-witness accounts of the events in question. Right of the map is a description, written by Hutchings, describing the event and the Collect Pond vessel itself. Dated and copyrighted: “Entered according to act of Congress in the year 1846 by John Hutchings in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the Southern District of N.Y.” Date: 1846[6] Quoted in: The Memorial History of the City of New-York: From Its First Settlement to the Year 1892, Vol. 3, ed. by James Grant Wilson (New York History Co., 1893)

References: "Collect Pond, Manhattan." New York Public Library: American Shores, Maps of the Mid Atlantic Region to 1850. 2002, http://www.nypl.org/research/midatlantic/geo_collect.html. Peters, Harry T., AMERICA ON STONE / THE OTHER PRINTMAKERS TO THE AMERICAN PEOPLE, p. 282

1846 Broadside of the Collect Pond, New York and Steam Boat ( Five Points )

[7] See the additional sources above, particularly: The Memorial History of the City of New-York: From Its First Settlement to the Year 1892, Vol. 3, ed. by James Grant Wilson (New York History Co., 1893)

[8] Here's a list of the posts:

1 comment:

If this map is in fact a model for maps printed at a later time we were not able to identify on the map the minute that had descended from him. Even so this is a piece of rare and unique of its kind and represents an important part of the history of five points.

Pond Filters

Post a Comment