Father and son challenge each other to believe that the generation that Daniel represents will be able to turn around all that we see around us that is going wrong, this generation that is unable to vote and deeply pessimistic about the ability of the elder generations who currently wield power to make things better. Tony says "Nothing manmade is inevitable: Chinese capitalism — unregulated profit accompanied by serial environmental catastrophe — is not the only possible future. ... If you want to change the world, you had better be willing to fight for a long time. And there will be sacrifices. Do you really care enough or are you just offended at disturbing pictures?" Daniel responds "We have no choice but to care enough. The sacrifices you foresee are nothing compared to the ones we will be forced to make if we sit back and wait." It's a good read: Generations in the Balance.

It also brings forth a topic that's been on my mind.

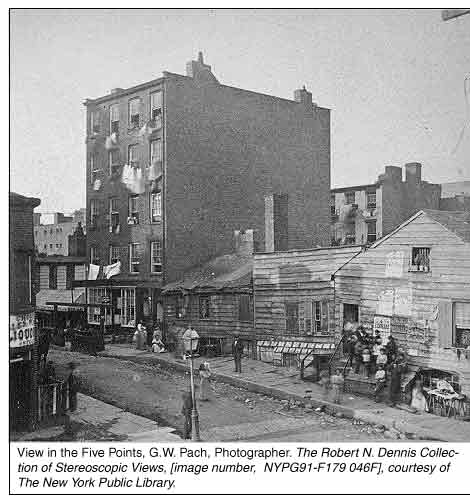

The Irish emigrants who came to New York City in the 1830s, '40s, and '50s had far less reason to hope for a better future than the young generation of which Daniel Judt is a member. While they lived in Ireland they knew only poverty, ignorance, and subservience. They had no experience of urban life, no political acumen, no knowledge of the many ways of earning and saving money. Yet within the span of one generation, from the 1850s to the 1880s, they managed to move well up from their starting point at the bottom of New York's social and economic scale.

They not only earned and saved their pennies from menial labor for New York's wealthier classes, but they also organized and carried out battles for equitable treatment. This transition did not come easily. They were failed subsistence farmers, rural paupers without knowledge of the world. Finding work that paid enough to support themselves and learning to survive in a big city were, each of them, huge accomplishments. That they could also eventually overcome prejudice against their habits, culture, and religious beliefs shows them to have had great persistence, resilience. They had the moxie which Daniel Judt seeks in his generation.

The remittances they sent back to the homeland shows their progress in gradually overcoming barriers to economic advancement. In rough orders of magnitude, the amounts Irish-Americans sent to Ireland grew from something less than $40,000 in 1834 to more than $3 million in 1870 and the cumulative amount for the period from 1850 to 1870 was not much less than $100 million. These amounts are not weighted to today's valuation, but the actual currency values of the time.[2] Even the poorest of the poor, those "assisted emigrants" from Lord Lansdowne's vast holdings in Kerry (about whom I wrote not long ago), were able to send money to family and friends they had left behind. So, for example, in 1851 Lansdowne's agent in Ireland was able to write to him: "The most cheering accounts are daily reaching us of their success in New York. Considerable sums of money have been already sent over in very small remittances of 20s or 30s each, and every letter which arrives brings new accounts of how well they fare and urging others to come over if they can."[3]

The social and political successes of the Irish-Americans in New York are well known. No group holding power gives it up gracefully, but the Protestants ascendant in New York society and politics were particularly resistant to pressures from Irish Catholic immigrants. British-American New Yorkers, so-called Anglo-Saxons, joined together in "nativist" attacks on the Irish whom many of them saw as competitors for low-paying jobs and whom they stigmatized as degraded, hopelessly immoral, and idolatrous. Their attacks bore great similarity to attacks made on freed slaves in New York a decade or so before. These bigots formed the core membership of the "native" American and Know-Nothing movements during the antebellum period. Partly in resistance to these attacks, Irish Catholics, more than any other European ethnic group, emphasized economic solidarity, collective action, and politics as keys to resisting discrimination and increasing their prominence in the political, cultural, and economic aspects in their newly adopted homeland.[4]

By the 1870s, with immigration having continued over the middle decades of the nineteenth century, New York had become the most Irish city in the US with more Irish-Americans than the population of Dublin. By the end of the century, they had become a dominant factor in many, perhaps most, aspects of life in the city.

One man's story helps illustrate this massive transition. As you read this extract from an inventive reconstruction by Rebecca Yamin notice that her subject, Peter McLoughlin, is a resident of the Five Points district who arrived before the famine Irish of the 1840s and '50s. As they would later on, he managed to save enough money to achieve a modest level of prosperity, but — belying the image of improvidence with which the Irish were tagged — he used his savings as capital to expand his wealth and also, through collective action, to help his fellow countrymen in their quest to follow the example he had set. His story was not typical since he was able to amass a fortune during his lifetime, and most immigrants considered themselves fortunate to have achieved much less. Still, it is an exemplary one since they, like him, advanced their condition through hard work and self-denial. They saved pennies, sent remittances back to Ireland, and stood together to give one another support.

Peter McLoughlin purchased 472 Pearl Street in 1839 for $16,400, running a liquor store on the ground floor of the old wooden house from 1838 until he replaced the building in the late 1840s. McLoughlin lived a few blocks away on Madison Street and apparently treated the Pearl Street property as an investment, the first of many he would make in the burgeoning city. By 1848, he had built a five-story brick tenement on his Pearl Street property, just in time to receive impoverished Irish immigrants who had fled their country in "Black 47," the most desperate year of the famine.Tyler Anbinder tells a similar tale regarding the next generation of immigrants. His subject is the well-known Tim Sullivan. Sullivan's story interests partly because, like many of his fellow countrymen, he saw politics as the best way to take advantage of both the solidarity and numerical preponderance of the city's Irish-Americans.

McLoughlin was concerned with the mass immigration and had been working since 1842 on the executive committee of the Irish Emigrant Society. By 1850, McLoughlin's tenement held about 20 households headed by either Irish women or men. Among them was McLoughlin's brother, Michael, who arrived in New York from Sligo in 1832. He eventually settled at 472 with his wife, Mary Fox, and like practically every other resident took in boarders to make ends meet in spite of the fact that most apartments included only two rooms. A mason, a grocer, and a laborer brought the number of souls in the McLoughlin household to five, but it was far from the largest. In addition to his wife and children, Thomas Peppard's household included four boarders, two probably working with the head of the household at shoemaking; Catherine Connell's household included five women in addition to herself; and Maurice Callaghan, a food vendor, and his family boarded Thomas Conner, fruit dealer, and Francis Bernard, a tailor. Widow Johnston had at least four women living with her, and Widow Berry shared her humble abode with a married couple, in addition to her two daughters.

For the greatly expanded number of people living on the lot (there were at least 100 in 1850), McLoughlin significantly upgraded the sanitary facilities. Following new and improved ideas about "convenience," he built an 11-foot diameter cesspool about 15 feet behind the tenement. Some sort of water system flushed wastes from adjacent privies into the cesspool, which was not hooked up to a sewer although water and sewer lines had been laid in Pearl Street in 1848, just about the time the tenement was built. A brick lined drain ran from an iron grate in the wall of the cesspool into a small sump located to the south, presumably to prevent overflow from going into the tenement basement.

McLoughlin died a rich man in 1854, leaving six house lots at Five Points and four vacant lots uptown at 109th Street and 2nd Avenue. He had been renting his liquor store on the ground floor of 472 Pearl Street since the late 1840s, turning his efforts to banking and good works. He worked as controller of the Citizens Savings Bank and served as the treasurer of the Roman Catholic Orphan Asylum for a number of years. At his death, his properties passed to his executors, John McLoughlin and Thomas Muldoon, but brother Michael apparently inherited some of the money since, a year later, he opened a savings account at the Emigrant Savings Bank with the not insubstantial sum of $2,000.

William Clinton bought 472 Pearl Street in 1864. Clinton, also an Irishman, increased the property's value by constructing a second tenement at the back of the lot. To do this, he transformed the already crowded backyard into a mere 20-x-25-foot courtyard, turning a deaf ear to health reformers' complaints about miserable sanitary conditions and the lack of air in New York's tenement districts. Although the number of residents did not increase appreciably, the ethnic mix changed over time. In 1880, a significant number of Italians lived alongside both first and second-generation Irish.

-- "Lurid Tales and Homely Stories of New York's Notorious Five Points; Archaeologists as Storytellers" by Rebecca Yamin. Historical Archaeology, Vol. 32, No. 1, 1998, pp. 74-85. Retrieved from jstor: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25616594

Here's part of Tim's story, as related by Tyler Anbinder. As Anbinder points out, Sullivan was a "Lansdowne emigrant" who settled in Five Points.

The fate of young Tim Sullivan, the bootblack and newsboy, reflects the myriad opportunities that New York offered to the Lansdowne immigrants and their children. In his various jobs delivering newspapers, Sullivan developed a network of contacts among the city's newsboys and periodical dealers. Even though by his teenage years he worked in the news plants themselves, he simultaneously became a newspaper distributor, because the distribution managers knew that Sullivan, through his web of newsboys, could guarantee that their papers would be sold throughout the city. "Every new newspaper that come out, I obtained employment on, on account of my connection with the news-dealers all over the City of New York," Sullivan recalled in 1902. His income from these operations must have been significant, because by his late teens he was ready to open his first saloon, and by his early twenties he purportedly had interests in three or four. Sullivan was also very popular, and at twenty-three, without any prior legislative experience, he was elected to the New York state assembly. Although first chosen for office as an insurgent running against the city's "Tammany Hall" Democratic organization, "Five Points Sullivan" soon began cooperating with Tammany and quickly moved up through the ranks. He eventually served in the state senate and the United States House of Representatives. By the turn of the century, this child of Lansdowne immigrants had become "Big Tim" Sullivan, "the political ruler of down-town New York." Some observers considered him the second most powerful politician in the city, after Tammany "boss" Richard Croker. Sullivan also became quite wealthy. Critics charged that his fortune had been built from payoffs exacted from gambling and prostitution syndicates in his district. But "Big Tim" insisted that he had never taken a bribe in his life and that his substantial income derived from shrewd investments in vaudeville theaters and other legitimate businesses. No matter what the origin of his fortune may have been, Sullivan remembered his humble origins and shared his wealth with his less prosperous constituents, giving away thousands of pairs of shoes and Christmas dinners each year.During excavation for a public building in what had formerly been the Five Points district, an enormous number of artifacts were unearthed by archaeologists searching in what had been cess pits. Only 18 of these hundreds of thousands of items survive today; the rest were being stored in the basement of Six World Trade center and were lost during the 9/11 attacks. The 18 pieces come from places were Irish-Americans made their homes in Five Points. They survived because they had been loaned out to the archdiocese of New York for an exhibition. The exhibition was canceled due the untimely death of Cardinal O'Connor's death. They're now on display at the South Street Seaport Museum. Here are images of two:

-- From Famine to Five Points: Lord Lansdowne's Irish Tenants Encounter North America's Most Notorious Slum by Tyler Anbinder, American Historical Review, Vol. 107, No. 2, April 2002.

----------

Some sources:

Immigrants in the City: New York's Irish and German Catholics by Jay P. Dolan, Church History, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Sep., 1972), pp. 354-368, retrieved from jstor: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3164221

The New York Irish ed. by Ronald H. Bayor and Timothy J. Meagher (JHU Press, 1997)

Irish American Solidarity

The Irish (in countries other than Ireland) In the United States

From Famine to Five Points: Lord Lansdowne's Irish Tenants Encounter North America's Most Notorious Slum by Tyler Anbinder, American Historical Review, Vol. 107, No. 2, April 2002.

The Catholic encyclopedia: an international work of reference on the constitution, doctrine, discipline, and history of the Catholic Church

----------

Notes:

[1] Judt, the elder, is a British historian, descendant of Lithuanian rabbis, professor at NYU, and frequent contributor to NYRB. He suffers from ALS and has written and been interviewed about the effect the disease has on him. Regarding Daniel's response to the attack on his integrity, see also: Shots Returned! Tony Judt's 15-Year-Old Son Just Schooled Michael Wolff and "Who Is This Clown?" NYU Prof. Tony Judt Asks, Denying Michael Wolff Allegation That He "Made Up" Son's Contribution To NYT Op-Ed Piece..

[2] See the article on the Irish in New York in The Catholic encyclopedia: an international work of reference on the constitution, doctrine, discipline, and history of the Catholic Church

[3] Quoted in From Famine to Five Points: Lord Lansdowne's Irish Tenants Encounter North America's Most Notorious Slum by Tyler Anbinder, American Historical Review, Vol. 107, No. 2, April 2002. Here's the context:

We do know that the Lansdowne immigrants had undergone a remarkable transformation in a few short years from destitute Irish peasants to moderately successful New Yorkers. In Ireland, they had been among the most wretched of that nation's inhabitants. The Lansdowne tenants survived six years of unrelenting hardship in Ireland during the famine, a period of privation far longer than that of the typical famine-era emigrant. In a period when hundreds of thousands of desperate and impoverished Irish men, women, and children fled to North America, the Lansdowne immigrants were singled out by observers on both sides of the Atlantic for their particularly dire circumstances. Many apparently perished in the "Lansdowne Ward" of New York Hospital, so-called because many of the marquis's former tenants died there soon after their arrival. Yet while these immigrants may have first settled in Five Points because they could afford nothing else, they chose to stay even after they could have easily moved to more respectable neighborhoods. In just a few years in New York, many of these once "unfortunate creatures" achieved a modicum of financial security. While Trench may have exaggerated the immigrants' fortunes when he talked of them returning with chains of gold, by 1860 a large number of the immigrants had in fact saved enough to purchase such baubles had they chosen to do so. ...[4] See Back to Ethnic America Irish American Solidarity.

A few things are certain. First, the degree of financial success achieved by the Lansdowne immigrants despite their decrepit surroundings suggests that the famine immigrants adapted to their surroundings far better and more quickly than we have previously imagined. After the initial year or so of adjustment, the Lansdowne immigrants stayed in Five Points not because they had to but because they chose to. In addition, the Lansdowne immigrants' story demonstrates the value of tracing the lives of famine-era immigrants back to Ireland, adding a transatlantic perspective that has generally been lacking in the field of immigration history. That Five Pointers from the Lansdowne estate achieved their modicum of financial security despite the extraordinary hardships (even by Irish standards) that they faced before, during, and immediately after their arrival in New York makes those monetary accomplishments all the more remarkable. Their saga demonstrates that we still have a lot to learn about how nineteenth-century immigrants adjusted to—and were transformed by—life in modern America.

No comments:

Post a Comment