For generations these Kerry paupers and their families had been subsisting on tiny plots of land, exploited by their landlords and treated no better than beasts of the field, in some cases possibly worse. Nothing was expected of them, no opportunities to advance were open to them, no education was made available to them. There were no wage-paying jobs to be had. Most could not read or write and many had Irish as their only language.

Their lives were brutal and they themselves, not surprisingly, brutish.

Their farming skills were medieval. Like medieval peasants or serfs, they married young and raised large families. As the world knows, they were also totally dependent on the potato for sustenance. It was a nourishing crop and not much else would grow in the rocky soil on which many of them lived.

Local practice did not restrict the subdivision of small holdings into smaller and yet smaller ones so that, even before the famine struck, many families could no long subsist on the land they rented.

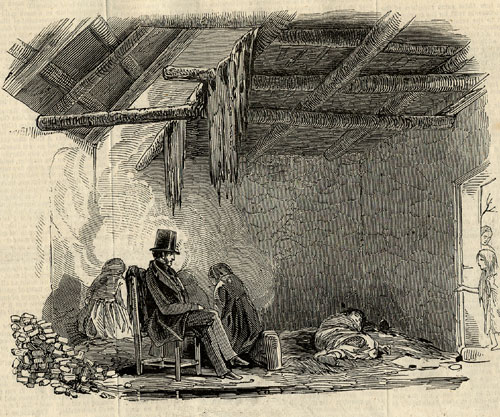

The lived in abominable shelters. A contemporary gave this description of a Kerry tenant's "home" about a decade before the famine:

Imagine four walls of dried mud (which the rain, as it falls, easily restores to its primitive condition) having for its roof a little straw or some sods, for its chimney a hole cut in the roof, or very frequently the door through which alone the smoke finds an issue. A single apartment contains father, mother, children and sometimes a grandfather and a grandmother; there is no furniture in the wretched hovel; a single bed of straw serves the entire family.Bad as things were before the famine, they were much, much worse when it suddenly struck.

Five or six half-naked children may be seen crouched near a miserable fire, the ashes of which cover a few potatoes, the sole nourishment of the family. In the midst of all lies a dirty pig, the only thriving inhabitant of the place, for he lives in filth. The presence of a pig in an Irish hovel may at first seem an indication of misery; on the contrary, it is a sign of comparative comfort. Indigence is still more extreme in a hovel where no pig is found... I have just described the dwelling of the Irish farmer or agricultural labourer.

-- Excerpt from a description of his tour in Ireland

by Gustave de Beaumont (1830s) quoted from the Foreign Monthly Review in The Mirror of literature, amusement, and instruction, Volume 34, ed by John Timbs (J. Limbird, 1839)

The water mold that caused Irish potatoes to rot in the field did not originate in Ireland but in Mexico. Irish Landowners had advance warning of its coming but took no action either to prevent its invasion of their properties or to make available alternative food sources for their tenants (though grain was available and could have been provided). Local authorities charged with assisting paupers were quickly overwhelmed and as many people probably died of starvation and disease within Ireland's Poor Law workhouses and while seeking "outdoor relief" as they did in the barren fields.[3]

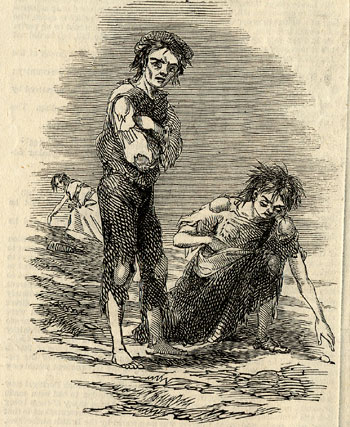

In the late 1840s, the Illustrated London News and other British papers sent sketch artists into the western counties of Ireland to make a visual record the famine conditions there.

Bridget O'Donnel and Children

The man who had been given charge of Lansdowne's Kerry estate wrote despairingly of this period: "The local gentry were paralyzed, the tradesmen were paralyzed, the people were paralyzed, and the cottiers and squatters and small holders, who now saw the consequences of their previous folly in unlimited subdivision, unable from hunger to work, and hopeless of any sufficient relief from extraneous sources, sank quietly down, some in their houses, some at the " relief works," and died almost without a struggle." -- Realities of Irish life by William Steuart Trench (Roberts Brothers, 1880)[4]

--------------

Some sources:

Assisted Emigration from the Shirley Estate in County Monaghan, 1846-1853 on bytown.net

Emigration from Europe, 1815-1930 Volume 11 of New studies in economic and social history, by Dudley Baines (Cambridge University Press, 1995)

Emigration and immigration: a study in social science by Richmond Mayo-Smith (C. Scribner's sons, 1912)

Pre-Famine Life on rootsweb

The Famine in Clare from The Illustrated London News, 1849-50: Condition of Ireland - Illustrations of the New Poor-Law from clarelibrary.ie

Views of the Famine, page on the famine at vassar.edu

Illustrated London News images at vassar.edu

A history of emigration from the United Kingdom to North America, 1763-1912 Issue 34 of Studies in economics and political science, by Stanley Currie Johnson (Routledge, 1914)

From Famine to Five Points: Lord Lansdowne's Irish Tenants Encounter North America's Most Notorious Slum by Tyler Anbinder

Lansdowne's Estate in Kenmare Assisted Emigration Plan, Shea Family History in Ireland, Dick Shea, December 2009

Eyewitness Accounts of the Famine

The Great Famine of 1845 - 1849

Irish Views of the Famine

Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 3rd Marquis of Lansdowne

The Night side of New York. A picture of the great metropolis after nightfall by Frank Beard (New York, J.C. Haney & Co. 1866)

-------------

Notes:

[1] Here's the news item:

Destitute Emigrants. — Several destitute emigrants who arrived in this city a few days ago by the ship Montezuma, from Liverpool, were found Monday afternoon in the streets, in a starving condition. They were taken to the [local police station], where they were provided with food, after which they were sent to the Commissioners of Emigration. These emigrants, it appears, were taken out of the poorhouses in Ireland, by Lord Lansdowne."[2] Lansdowne's agent, the author of the plan, described it in a somewhat self-serving memoir he wrote some years later:

-- New-York Daily Tribune, Wednesday, March 19, 1851.

The remedy I proposed was as follows: that he [Lansdowne] should forthwith offer free emigration to every man, woman and child now in the poor-house or receiving relief and chargeable to his estate. That I had been in communication with an Emigration Agent, who had offered to contract to take them to whatever port in America each pleased, at a reasonable rate per head. That even supposing they all accepted this offer, the total, together with a small sum per head for outfit and a few shillings on landing would not exceed from £13,000 to £14,000, a sum less than it would cost to support them in the workhouse for a single year. That in the one case he would not only free his estate of this mass of pauperism which had been allowed to accumulate upon it, but would put the people themselves in a far better way of earning their bread hereafter, whereas by feeding and retaining them where they were, they must remain as a millstone around the neck of his estate, and prevent its rise for many years to come; and I plainly proved that it would be cheaper to him, and better for them, to pay for their emigration at once, than to continue to support them at home.Workhouses and the Poor Law are explained here: 650x4green.gif (935 bytes) Prelude to Famine 3: Economics

-- Realities of Irish life by William Steuart Trench (Roberts Brothers, 1880)

[3]See Phytophthora infestans, the wikipedia article on the potato blight; and see Potato Blight and Prelude to Famine 3: Economics on wesleyjohnston.com.

[4] Trench's memoir is self-serving and not uncontroversial, but he gives vivid descriptions from an overseer's point of view. Some excerpts:

The district of Kenmare at that period, — January, 1850, — was not in a desirable condition. "The famine," in the strict acceptation of the term, was then nearly over, but it had left a trail behind it, almost as formidable as its presence.

The estate of the Marquis of Lansdowne in the Union of Kenmare had at this time been much neglected by its local manager. It consists of about sixty thousand acres, and comprises nearly one third of the whole union. No restraint whatever had been put upon the system of subdivision of land. Boys and girls intermarried unchecked, each at the age of seventeen or eighteen, without thinking it necessary to make any provision whatever for their future subsistence, beyond a shed to lie down in, and a small plot of land whereon to grow potatoes. Innumerable squatters had settled themselves, unquestioned, in huts on the mountain sides and in the valleys, without any sufficient provision for their maintenance during the year. ... The estate, in fact, was swamped with paupers.

Half Ireland was stunned by the suddenness of the calamity, and Kenmare was completely paralyzed. Begging, as of old, was now out of the question, as all were nearly equally poor; and many of the wretched people succumbed to their fate almost without a struggle.

The agent of the estate, who on my first arrival was my chief informant, did not seem to consider that any one in particular was to blame for this. He talked of it as "the hand of God." The whole thing had come so suddenly, and all those residing at Kenmare were so entirely unprepared, and incapable of meeting it, that an efficient remedy was utterly out of the question.

The magnitude of the suffering seemed to paralyze all local efforts to avert it.... And thus almost in the midst of plenty, — for there was abundance of corn within a few miles distant, famine stalked unmolested through the glens and mountains of Glanerought.

When I first reached Kenmare in the winter of 1849-50, the form of destitution had changed in some degree; but it was still very great. It was true that people no longer died of starvation; but they were dying nearly as fast of fever, dysentery, and scurvy within the walls of the work-house. Food there was now in abundance; but to entitle the people to obtain it, they were compelled to go into the work-house and "auxiliary sheds," until these were crowded almost to suffocation. And although out-door relief had also been resorted to in consequence of the impossibility of finding room for the paupers in the houses, yet the quantity of food given was so small, and the previous destitution through which they had passed was so severe, that nearly as many died now under the hands of the guardians, as had perished before by actual starvation.

1 comment:

Dear Jeff,

This is such an interesting article and with your authorisation i would like to quote in for my homework for Irish Studies in the Sorbonne Nouvelle. If you are in agreement

Could you please let me have your full name, date of article etc.

Many thanks in advance

Best regards

Patricia Killeen

triciakilleen@yahoo.fr

Post a Comment