Natalie Bennett, an Australian who's been living in London for the past seven years, writes two interesting blogs, Philobiblon and My London Your London. She says: "I'm a generalist. I want to know about everything, but not in too much detail."

Natalie Bennett, an Australian who's been living in London for the past seven years, writes two interesting blogs, Philobiblon and My London Your London. She says: "I'm a generalist. I want to know about everything, but not in too much detail." Philobiblon focuses on history, science, and art, particularly from a woman's point of view (as she says "always feminist"). The blog's name comes from a Medieval book by called The Love of Books, Being the Philobiblon of Richard de Bury.

Philobiblon focuses on history, science, and art, particularly from a woman's point of view (as she says "always feminist"). The blog's name comes from a Medieval book by called The Love of Books, Being the Philobiblon of Richard de Bury.My London Your London contains sections on Natalie Bennett says "I've lived in London for seven years, and I still love every minute of it. With the theatres, the museums and galleries, the streets dripping with history, there's so much here that many visitors miss."

Here are extracts from a recent post on an exhibition at the British Library:

Listening to history: Fashion Lives at the British Library

Lily Silberberg's story might be that of the 20th century - the good side of the period, not its darker hue. She was born in London in 1929, to Jewish parents whose had fled Russia after the Revolution. Her father was a "journeyman tailor", her mother an outworker spending her evenings sewing buttonholes late into the night by the light of a gas lamp.

Yet by the time Lily retired, well into her seventies, she had a full, satisfying, successful career behind her. She'd been a respected higher education lecturer, published a book, The Art of Dress Modelling, and spent the last years of her working life teaching her skills to the Bangladeshi community in Tower Hamlets.

When I heard of the exhibition I feared a parade through the usual glamorous suspects, but this is a show on the other side of fashion, the behind-the-scene characters who do all of the work while designers swan around collecting the glory.

Here's a post from Philobiblon that I like, though they're all good:

But where's the loo?

It was in the Indian city of Varanasi that I first realised that provision of lavatory facilities is a feminist issue. Simply there are none, or at least weren't when I was there eight or so years ago. For the men this wasn't a problem; they just went anywhere. (One of the many things in Varanasi that contribute to it being a total hole of a place - if someone tells you to put it on their tour itinerary, ignore them.)

Women's movements were effectively restricted to the range of their home, and the homes of any relatives or friends that might be along their intended route.

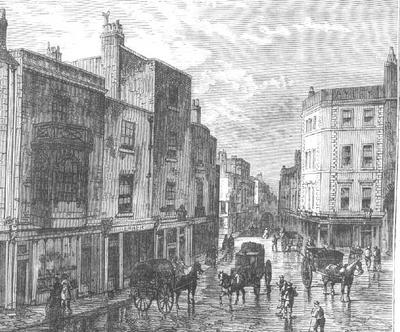

The above image is of London, Kensington High Street, about 1860. Then the same restrictions applied on Englishwomen."The middle-class diarist Ursula Bloom explained that when she was a girl 'there were no public lavatories in England, and it was thought the height of indecency ever to desire anything of the sort.' She went on to recall that 'in London fashionable ladies went for a day's shopping with no hope of any relief for those faithful tides of nature until they returned home again.' ...This also brings back memories of my agricultural science studies (my first degree - my only explanation is that I was only 17 when I chose it). We were the first year in which women were a majority, and the first-year excursion included virtually no facilities. Only wholesale revolts forced the bus to wait for the long queue using each farmer's one and only loo. (And this was in northwest NSW, so no trees as an alternative option.)

Edith Hall, a working-class woman who was born in Middlesex in 1908, recalled that while walking with her mother along the Thames during the First World War, she asked, 'There aren't many lavatories for ladies, are there?' Her mother matter-of-factly answered: ' Well, we are more lucky now ... There didn't seem to be any at all when we were young ... Either ladies didn't go out or ladies didn't 'go'.' " (Quoted in Shopping for Pleasure: Women in the Making of London's West End, Erika Diane Rappaport, Princeton University Press, 2000, p. 82)

*Image from Old and New London, By Edward Walford, Illustrated, Part 49, hard to date, but perhaps 1890s.)

No comments:

Post a Comment